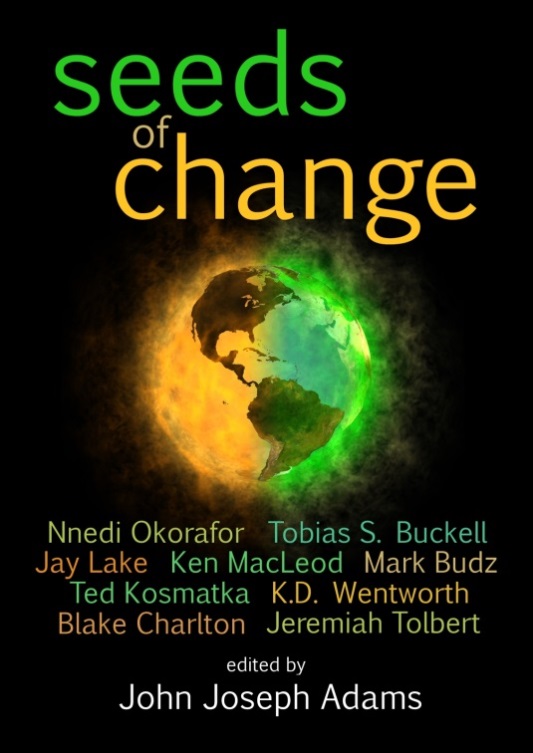

Книга: Seeds of Change

John Joseph Adams

Ursula K. Le Guin once wrote, “Science fiction is not predictive; it is descriptive”—which is to say that it uses the future as a lens to examine the here and now. Sometimes the paradigms of the present must be challenged, and one of the ways to do that is through science fiction.

I asked the contributors to this anthology to write about paradigm shifts—technological, scientific, political, or cultural—and how individuals and societies deal with such changes. The idea is to challenge our current paradigms and speculate on how they might evolve in the future, either for better or for worse.

Several of the stories approach the theme directly with current, topical issues—Ted Kosmatka tackles racism; Tobias S. Buckell explores the importance of voting; K. D. Wentworth takes a humorous look at a possible recycling revolution; Jay Lake ponders a world-changing technological advance and the market forces conspiring against it; Nnedi Okorafor takes us to the Niger Delta, where oil is a top commodity and people a secondary consideration.

After selecting the table of contents, I asked the contributors to describe how they interpreted the theme. Responses were thoughtful and diverse, but perhaps Blake Charlton captured the essence of the anthology best: “Fiction can be a mode of social change,” he said. “The most important revolutions begin quietly; the perception of injustice and suffering must precede any action against them.”

It is my hope that reading these stories inspires some to plant their own seeds of change—that when we see something wrong, we’ll do something about it, whether that means writing to your representative in Congress or researching a cure for a disease or simply speaking out against inequality and prejudice. We’re all in this together—and the first step toward change can begin with any one of us.

Ted Kosmatka

THEY CAME FROM test tubes. They came pale as ghosts with eyes as blue-white as glacier ice. They came first out of Korea.

I try to picture David’s face, but I can’t. They’ve told me this is temporary—a kind of shock that happens sometimes when you’ve seen a person die that way. Although I try to picture David’s face, it’s only his pale eyes I can see.

My sister squeezes my hand in the back of the limo. “It’s almost over,” she says.

Up the road, against the long, wrought iron railing, the protestors grow excited as our procession approaches. They’re standing in the snow on both sides of the cemetery gates, men and women wearing hats and gloves and looks of righteous indignation, carrying signs I refuse to read.

My sister squeezes my hand again. Before today I had not seen her in almost four years. But today she helped me pick out my black dress. She helped me with my stockings and my shoes. She helped me dress my son, who is not yet three, and who doesn’t like ties—and who is now sleeping on the seat across from us without any understanding of what he’s lost.

“Are you going to be okay?” my sister asks. She is watching the protestors.

“No,” I say. “I don’t think I am.”

The limo slows as it turns onto cemetery property, and the mob rushes in, shouting obscenities. Protestors push against the sides of the vehicle.

“You aren’t wanted here!” someone shouts, and then an old man’s face is against the glass, his eyes wild. “God’s will be done!” he shrieks. “For the wages of sin is death.”

The limo rocks under the press of the crowd, and the driver accelerates until we are past them, moving up the slope toward the other cars.

“What’s wrong with them?” my sister whispers. “What kind of people would do that on a day like today?”

You’d be surprised, I think. Maybe your neighbors. Maybe mine. But I look out the window and say nothing. I’ve gotten used to saying nothing.

* * * *

SHE’D SHOWN UP at my house this morning a little after 6:00. I’d opened the door, and she stood there in the cold, and neither of us spoke, neither of us sure what to say after so long.

“I heard about it on the news,” she said finally. “I came on the next plane. I’m so sorry, Mandy.”

There are things I wanted to say then—things that rose up inside of me like a bubble ready to burst, and I opened my mouth to scream at her, but what came out belonged to a different person: it came out a pathetic sob, and she stepped forward and wrapped her arms around me, my sister again after all these years.

The limo slows near the top of the hill, and the procession tightens. Headstones crowd the roadway. I see the tent up ahead, green; its canvass sides billowing in and out with the wind, like a giant’s breathing. Two-dozen gray folding chairs crouch in straight rows beneath it.

The limo stops.

“Should we wake the boy?” my sister asks.

“I don’t know.”

“Do you want me to carry him?”

“Can you?”

She looks at the child. “He’s only three?”

“No,” I say. “Not yet.”

“He’s big for his age. I mean, isn’t he? I’m not around kids much.”

“The doctors say he’s big.”

My sister leans forward and touches his milky white cheek. “He’s beautiful,” she says. I try not to hear the surprise in her voice. People are never aware of that tone when they use it, revealing what their expectations had been. But I’m past being offended by what people reveal unconsciously. Now it’s only intent that offends. “He really is beautiful,” she says again.

“He’s his father’s son,” I say.

Ahead of us, mourners climb from their cars. The priest is walking toward the grave.

“It’s time,” my sister says. She opens the door and we step out into the cold.

* * * *

THEY CAME FIRST out of Korea. But that’s wrong, of course. History has an order to its telling. It would be more accurate to say it started in Britain. After all it was Harding who published first; it was Harding who shook the world with his announcement. And it was Harding who the religious groups burned in effigy on their church lawns.

Only later did the Koreans reveal they’d accomplished the same goal two years before, and the proof was already out of diapers. And it was only later, much later, that the world would recognize the scope of what they’d done.

When the Yeong Bae fell to the People’s Party, the Korean labs were emptied, and there were suddenly thousands of them—little blond and red-haired orphans, pale as ghosts, starving on the Korean streets as society crumbled around them. The ensuing wars and regime changes destroyed much of the supporting scientific data—but the children themselves, the ones who survived, were incontrovertible. There was no mistaking what they were.

It was never fully revealed why the Yeong Bae had developed the project in the first place. Perhaps they’d been after a better soldier. Or perhaps they’d done it for the oldest reason: because they could.

What is known for certain is that in 2001 disgraced stem cell biologist Hong Yong-joon cloned the world’s first dog, an afghan. In 2006, he revealed that he’d tried and failed to clone a mammoth on three separate occasions. Western labs had talked about it, but the Koreans had actually tried. This would prove to be the pattern.

In 2016 the Koreans finally succeeded, and a mammoth was born from an elephant surrogate. Other labs followed. Other species. The Pallid Beach Mouse. The Pyrenean Ibex. And older things. Much older.

The best scientists in the US had to leave the country to do their work. US laws against stem cell research didn’t stop scientific advancement from occurring; it only stopped it from occurring in the United States. Instead, Britain, China, and India won patents for the procedures. Many cancers were cured. Most forms of blindness, MS, and Parkinson’s. Rich Americans had to go overseas for procedures that had become commonplace in other parts of the industrialized world. When Congress eventually legalized the medical procedures, but not the lines of research which lead to them, the hypocrisy was too much, and even the most loyal American cyto-researchers left the country.

Harding was among this final wave, leaving the United States to set up a lab in the UK. In 2013, he was the first to bring back the Thylacine. In the winter of 2015, someone brought him a partial skull from a museum exhibit. The skull was doliocephalic—long, low, large. The bone was heavy, the cranial vault enormous—part of a skullcap that had been found in 1857 in a quarry in the Neander valley.

* * * *

SNOW CRUNCHES UNDER our feet as my sister and I move outside the limo. The wind is freezing, and my legs grow numb in my thin slacks. It is fitting he is being buried on a day like today; David was never bothered by the cold.

My sister gestures toward the limo’s open door. “Are you sure you want to bring the boy? I could stay with him in the car.”

“He should be here,” I say. “He should see it.”

“He won’t understand.”

“No, but later he might remember he was here,” I say. “Maybe that will matter.”

“He’s too young to remember.”

“He remembers everything.” I lean into the shadows and wake the boy. His eyes open like blue lights. “Come, Sean, it’s time to wake up.”

He rubs a pudgy fist into his eyes and says nothing. He is a quiet boy, my son. Out in the cold, I pull a hat down over his ears. He's still half asleep as we climb the hill. The boy walks between my sister and me, holding our hands.

At the top, Dr. Michaels is there to greet us, along with other faculty from Stanford. They offer their condolences, and I work hard not to break down. Dr. Michaels looks like he hasn’t slept. David was his best friend. I introduce my sister and hands are shaken.

“You never mentioned you had a sister,” he says.

I only nod. Dr. Michaels looks down at the boy and tugs the child’s hat.

“Do you want me to pick you up?” he asks.

“Yeah.” Sean’s voice is small and scratchy from sleep. It is not an odd voice for a boy his age. It is a normal voice. Dr. Michaels lifts him, and the child’s blue eyes close again.

We stand in silence in the cold. Mourners gather around the grave.

“I still can’t believe it,” Dr. Michaels says. He’s swaying slightly, unconsciously rocking the boy. It is something only a man who has been a father would do, though his own children are grown.

“It’s like I’m another kind of person now,” I say. “Only nobody's told me how to be her yet.”

My sister grabs my hand, and this time I do break down. The tears burn in the cold.

The priest clears his throat; he’s about to begin. In the distance the sounds of protestors grows louder, the rise and fall of their chants not unpleasant—though from this distance, thankfully, I cannot make out the hateful words.

* * * *

WHEN THE WORLD first learned of the Korean children, it sprang into action. Humanitarian groups swooped into the war-torn area, monies exchanged hands, and many of the children were adopted out to other countries. They went to prosperous households in America, and Britain, and different countries all over the globe—a new worldwide Diaspora. They were broad, thick-limbed children; usually slightly shorter than average, though there were startling exceptions to this.

They looked like members of the same family, and some of them, assuredly, were more closely related than that. There were more children, after all, than there were fossil specimens from which they’d derived. Duplicates were inevitable.

From what limited data remained of the Koreans’ work, there had been more than sixty different DNA sources. Some even had names: the Old Man La Chappelle aux Saints, Shanidar IV and Vindija. There was the handsome and symmetrical La Ferrassie specimen. And even Amud I. Huge Amud I, who had stood 1.8 meters tall and had a cranial capacity of 1740ccs—the largest Neanderthal ever found.

The techniques perfected on dogs and mammoths had worked easily, too, within the genus Homo. Extraction, then PCR to amplify. After that came IVF with paid surrogates. The success rate was high, the only complication frequent cesarean births. And that was one of the things popular culture had to absorb, that Neanderthal heads were larger.

Tests were done. The children were studied and tracked and evaluated. All lacked normal dominant expression at the MC1R locus—all were pale-skinned, freckled, with red or blonde hair. All were blue-eyed. All were Rh negative.

I was six years old when I first saw a picture. It was the cover of Time—what is now a famous cover. I’d heard about these children but had never seen one—these children who were almost my age, from a place called Korea; these children who were sometimes called ghosts.

The magazine showed a pale, red-haired Neanderthal boy standing with his adoptive parents, staring thoughtfully up at an outdated anthropology display at a museum. The wax Neanderthal man in the display carried a club. He had a nose from the tropics, dark hair, olive-brown skin and dark brown eyes. Before Harding’s child, the museum display designers had supposed they knew what primitive looked like, and they had supposed it was decidedly swarthy.

Never mind that Neanderthals had spent ten times longer in light-starved Europe than a typical Swede’s ancestors.

The boy looked up at the display with a confused expression.

When my father walked into the kitchen and saw the Time cover, he shook his head in disgust. “It’s an abomination,” he said.

I studied the boy’s jutting face. I’d never seen anyone with face like that. “Who is he?”

“A dead-end. Those kids are going to be a drain for the rest of their lives. It’s not fair to them, really.”

That was the first of many pronouncements I’d hear about the children.

Years passed and the children grew like weeds—and as with all populations, the first generation exposed to a western diet grew several inches taller than their ancestors. While they excelled at sports, their adopted families were told they could be slow learners and might be prone to aggression. The families were even told, in the beginning, that the children could be antisocial and might never fully grasp the nuances of complex language. They were primitive after all.

A prediction which turned out to be as accurate as the museum displays.

* * * *

WHEN I LOOK up, the priest’s hands are raised into the cold, white sky. “Blessed are you, O God our father; praised be your name forever.” He breathes smoke, reading from the book of Tobit.

It is a passage I’ve heard at both funerals and marriage ceremonies, and this, like the cold on this day, is fitting. “Let the heavens and all your creations praise you forever.”

The mourners sway in the giant’s breathing of the tent.

I was born Catholic, but found little use for organized religion in my adulthood. Little use for it, until now, when its use is so clearly revealed—and it is an unexpected comfort to be part of something larger than yourself; it is a comfort to have someone to bury your dead.

Religion provides a man in black to speak words over your loved one’s grave. It does this first. If it does not do this, it is not religion.

“You made Adam and you gave him your wife Eve to be his love and support; and from these two, the human race descended.”

They said together, Amen, Amen.

* * * *

THE DAY I learned I was pregnant, David stood at our window, huge, pale arms draped over my shoulders. He touched my stomach as we watched a storm coming in across the lake.

“I hope the baby looks like you,” he said in his strange, nasal voice.

“I don’t.”

“No, it would be easier if the baby looks like you. He’ll have an easier life.”

“He?”

“I think it’s a boy.”

“And is that what you’d wish for him, to have an easy life?”

“Isn’t that what every parent wishes for?”

“No,” I said. I touched my own stomach. I put my small hand over his large one. “I hope our son grows to be a good man.”

* * * *

I’D MET DAVID at Stanford when he walked into class five minutes late.

He had arms like legs. And legs like torsos. His torso was the trunk of an oak— seventy-five years old, grown in the sun. A full-sleeve tattoo swarmed up one bulging, ghost-pale arm, disappearing under his shirt. He had an earring in one ear, and a shaved head. A thick red goatee balanced the enormous bulk of his convex nose and gave some dimension to his receding chin. The eyes beneath his thick brows were large and intense—as blue as a husky’s.

It wasn’t that he was handsome, because I couldn’t decide if he was. It was that I couldn’t take my eyes off him. I stared at him. All the girls stared at him.

He sat near the aisle and didn’t take notes like the rest of the students. As far as I could tell, he didn’t even bring a pen.

On the second day of class, he sat next to me. I couldn’t think. I didn’t hear a single word the professor said. I was so aware of the man sitting next to me, his big arms folded in front of him like crossed thighs. He took up a seat and a half, and his elbow kept brushing mine.

It was me who spoke first, a whisper. “You don’t care if you fail.” It wasn’t a question.

“Why do you say that?” He never looked at me and replied so quickly that I realized we’d already been in a kind of conversation, sitting here, without speaking a word.

“Because you aren’t taking notes,” I said.

“Ah, but I am.” He tapped his temple with a thick index finger.

He ended up beating me on the first two tests, but I beat him on the third.By the third test, I’d found a good way to distract him from studying.

It was harder for them to get into graduate programs back then. There were quotas—and like Asians, they had to score better to get accepted.

There was much debate over what name should go next to the race box on their entrance forms. The word “Neanderthal” had evolved into an epithet over the previous decade. It became just another N-word polite society didn’t use.

I’d been to the clone rights rallies. I’d heard the speakers. “The French don’t call themselves Cro-Magnons, do they?” the loudspeakers boomed.

And so the name by their box had changed every few years, as the college entrance questionnaires strove to map the shifting topography of political correctness. Every few years, a new name for the group would arise—and then a few years later sink again under the accumulated freight of prejudice heaped upon it.

They were called Neanderthals at first, then archaics, then clones—then, ridiculously, they were called simply Koreans, since that was the country in which all but one of them had been born. Sometime after the word “Neanderthal” became an epithet, there was a movement by some militants within the group to reclaim the word, to use it within the group as a sign of strength.

But over time, the group gradually came to be known exclusively by a name that had been used occasionally from the very beginning, a name which captured the hidden heart of their truth. Among their own kind, and finally, among the rest of the world, they came to be known simply as the ghosts. All the other names fell away, and here, finally, was a name that stayed.

* * * *

IN 2033, THE first ghost was drafted into the NFL. What modern weight training could do to Neanderthal physiology was nothing short of astonishing.

He stood 5’10’’ and weighed almost 360 lbs. He wore his red hair braided tight to his head, and his blue-white eyes shone out from beneath a helmet that had been specially designed to fit his skull. He spoke three languages. By 2035—the year I met David—the front line of every team in the league had one. Had to have one, to be competitive. They were the highest paid players in sports.

As a group, they accumulated wealth at a rate far above average. They accumulated degrees, and land, and power. The men—beginning mostly during their youth, and continuing after—accumulated women, and subsequently, children. And they accumulated, finally, the attentive glare of the racists, who found them a group no longer to be ignored.

In the 2040 Olympics, ghosts took gold in wrestling, in power lifting, in almost every event in which they were entered. Some individuals took golds in multiple sports, in multiple areas.

There was an outcry from the other athletes who could not hope to compete. There were petitions to have ghosts banned from competition. It was suggested they should have their own Olympics, distinct from the original. Lawyers for the ghosts pointed out, carefully, tactfully, that out of the fastest 400 times recorded for the 100 yard dash, 386 had been achieved by persons of at least partially sub-Saharan African descent, and nobody was suggesting they get their own Olympics.

Of course, racist groups like the KKK and the neo-Nazis actually liked the idea and advocated just that. Blacks, too, should compete against their own kind, get their own Olympics. After that, the whole matter degenerated into chaos.

* * * *

ONE NIGHT, I brought a picture home from work. I turned the light on over the bed, waking him.

“Smile,” I told him.

“Why?” David asked.

“Just do it.”

He smiled. I looked at the picture. Looked at him.

“It’s you,” I said.

Still smiling, he snatched the picture from my hand. “What is this?”

When he looked at the picture, his face changed. “Where’d you get this?” he snapped.

“It’s a photocopy from one of the periodicals in the archive. From one of the early studies at Amud.”

“Why do you think it’s me? This could be any of us.”

“The bones,” I said.

He crinkled up the paper and threw it across the room. “You can’t see my bones.”

“Teeth,” I said. “Are bones I can see.”

“That’s not me.” He rolled onto his side. “I’m me.”

And then I realized something. I realized that he’d already known he was Amud. And I realized, too, why he kept his head shaved—because there must have been another two or three of them out there, other athletes whose faces he recognized from the mirror, and shaving his head kept him distinct.

In some complex way, I’d embarrassed him. “I’m sorry,” I said. I ran my hand across his bare shoulder, up his broad neck to his jaw. I leaned down, and nibbled on his ear. “I’m sorry,” I whispered.

* * * *

BUT SOME THINGS you learn, you wish you could unlearn.

Like Diane, the new researcher from down the hall, leaning over my shoulder. “I realize it may be politically incorrect,” she said, then paused. Or perhaps I put the pause in there. Perhaps I heard what wasn’t there, because I am so used to what came next, in its almost endless variation. And how I hated that term, politically incorrect, hated the shield it gave racists who got to label themselves politically incorrect, instead of admitting what they really were. Even to themselves.

“I know it may be politically incorrect,” she said, then paused. “But sometimes I just wish those slope-heads would stop stirring up trouble all the time. I mean, you’d think they’d be grateful.”

I said nothing. I wished I could unlearn this about her.

I heard David’s voice in my head, peace at all costs.

But David, I thought, you don’t have to hear it, the leaned-forward, look-both-ways, confidential revelations—the inside talk from people who don’t know you’re outside, way outside. People look at you, David, and have sense enough not to say something.

And the new researcher continued, “I know the coalition is upset about what alderman Johnson said, but he’s entitled to his opinion.”

“And people are entitled to respond to that opinion,” I said.

“Sometimes I think people can be too sensitive.”

“I used to think that too,” I said. “But it’s a fallacy.”

“It is?”

“Yes, it is impossible to be too sensitive.”

“What do you mean?”

“Each person is exactly as sensitive as life experience has made them. It is impossible to be more so.”

* * * *

WHEN I WAS growing up, I helped my grandfather prune his apple trees in Indiana. The trick, he told me, was telling which branches helped grow the fruit, and which branches didn’t. Once you’ve studied a tree, you got a sense of what was important. Everything else can be pruned as useless baggage.

You can divest yourself of your identity in much the same way. Let it fall to the ground at your feet. You look at your child’s face, and you don’t wonder whose side you’re on. You know. That side.

I read in a sociology book that when someone in the privileged majority marries a minority, they take on the social status of that minority group. It occurred to me how the universe is a series of concentric circles, and you keep seeing the same shapes and processes wherever you look. Atoms are little solar systems; highways are a nation’s arteries, streets its capillaries—and the social system of humans follows Mendelian genetics, with dominants and recessives. Minority ethnicity is the dominant gene when part of a heterozygous couple.

* * * *

THERE ARE MANY Neanderthal bones in the Field Museum.

Their bones are different than ours. It is not just their big skulls, or their short, powerful limbs; virtually every bone in their body is thicker, stronger, heavier. Each vertebrae, each phalange, each small bone in the wrist, is thicker than ours. And I have wondered sometimes, when looking at those bones, why they need skeletons like that. All that metabolically expensive bone and muscle and brain. It had to be paid for. What kind of life makes you need bones like chunks of rebar? What kind of life makes you need a sternum half an inch thick?

During the Pleistocene, glaciers had carved their way south across Europe, isolating animal populations behind a curtain of ice. Those populations either adapted to the harsh conditions, or they died. Over time, the herd animals grew massive, becoming more thermally efficient, with short, thick limbs, and heavy bodies—and so began the age of the Pleistocene mega-fauna. The predators too, had to adapt. The saber-tooth cat, the cave bear. They changed to fit the cold, grew more powerful in order to bring down the larger prey. What was true for other animals was true for genus Homo, nature’s experiment, the Neanderthal—the ice age's ultimate climax predator.

* * * *

“A READING FROM the first letter of Saint Paul to the Corinthians.” The priest clears his throat. “Brothers and sisters: strive eagerly for the greatest spiritual gifts. But I shall show you a still more excellent way. If I speak in human and angelic tongues but have not love, I am a resounding gong, or a clashing cymbal.”

I watch the priest’s face while he speaks, this man in black.

“And if I have the gift of prophecy and comprehend all the mysteries and all knowledge; if I have all faith so as to move mountains, but do not have love, I am nothing.”

Dr. Michaels is still rocking my son in his arms. The boy is awake now. His blue eyes move to mine.

“Love bears all things, believes all things, hopes all things, endures all things.”

* * * *

THREE DAYS AGO, the day David died, I woke to an empty bed. I found him naked at the window in our living room, looking out into the winter sky, his leonine face wrapped in shadow.

From behind, I could see the V of his back against the gray light. I knew better than to disturb him. He became a silhouette against the sky, and in that instant, he was something more and less than human—like some broad human creature adapted for life in extreme gravity. A person built to survive stresses that would crush a normal man.

He turned back toward the sky. “There’s a storm coming today,” he said.

* * * *

THE DAY DAVID died, I woke to an empty bed. I wonder about that.

I wonder if he suspected something. I wonder what got him out of bed early. I wonder at the storm he mentioned, the one he said was coming.

If he’d known the risk, we never would have gone to the rally—I’m sure of that, because he was a cautious man. But I wonder if some hidden, inner part of him didn’t have its ear to the railroad tracks; I wonder if some part of him didn’t feel the ground shaking, didn’t hear the freight train barreling down on us all.

We ate breakfast that morning. We drove to the babysitter’s and dropped off our son. David kissed him on the cheek and tousled his hair. There was no last look, no sense this would be the final time. David kissed the boy, tousled his hair, and then we were out the door, Mary waving goodbye.

We drove to the hall in silence. David's mind was on the coming afternoon and the speech he had to give. We parked our car in the crowded lot, ignoring the counter-rally already forming across the street.

We shook hands with other guests and found our way to the assigned table. It was supposed to be a small luncheon, but the alderman's inflammatory statements, and his refusal to apologize, had swelled the crowd.

Up on the podium, David’s expression changed. Before his speeches, there was this moment, this single second, where he glanced out over the crowd, and his eyes grew sad.

David closed his eyes, opened them, and spoke. He began slowly. He spoke of the flow of history and the symmetry of nature. He spoke of the arrogance of ignorance; and in whispered tones, he spoke of fear. “And out of that simmering fear,” he said. “grows enmity.” He let his eyes wander over the crowd. “They hate us because we’re different,” he said, voice rising for the first time. “Always it works this way, wherever you look in history. And always we must work against it. We must never give in to violence. But we are right to fear, my friends. We must be vigilant, or we’ll lose everything we’ve gained for our children, and our children’s children.” He paused.

The specific language of this speech was new to me, but not the message. David pulled the words out of his head as he went—building energy from the ground up. He continued for another ten minutes before finally going into his close.

“They’ve talked about restricting us from athletic competition," he said, voice booming. “They’ve eliminated us from receiving most scholarships. They’ve limited our attendance of law schools, and medical schools, and PhD programs. These are the soft shackles they’ve put upon us, and we cannot sit silently and let it happen.”

The crowd erupted into applause. David lifted his hands to silence them and he walked back to his seat. Other speakers took the podium, but none with David’s eloquence. None with his power.

When the last speaker sat, dinner was brought out and we ate. An hour later, when the plates were clean, more hands were shaken, and people started filing out to their cars. The evening was over.

David and I took our time, talking with old friends, but we eventually worked our way into the lobby. Ahead of us, out in the parking lot, there was a commotion. The counter-rally had grown. Somebody mentioned vandalized cars, and then Tom was leaning into David’s ear, whispering as we passed through the front doors and out into the open air.

It started with thrown eggs. Thomas turned, egg-white drooling down his broad chest. The fury in his eyes was enough to frighten me. David rushed forward and grabbed his arm. There was a look of surprise on some of the faces in the crowd, because even they hadn’t expected anybody to throw things—and I could see, too, the group of young men, clumped together near the side of the building, eggs in hand, mouths open—and it was like time stopped, because the moment was fat and waiting—and it could go any way, and an egg came down out of the sky that was not an egg, but a rock, and it struck Sarah Mitchell in the face—and the blood was red and shocking on her ghost-white skin, and the moment was wide open, time snapping back the other way—everything moving too fast, all of it happening at the same time instead of taking turns the way events are supposed to. And suddenly David’s grip on my arm was a vise, physically lifting me, pulling me back toward the building, and I tried to keep my feet while someone screamed.

“Everybody go back inside!” David shouted. And then another woman screamed, a different kind of noise, like a shout of warning—and then I heard it, a shout that was a roar like nothing I’d ever heard before—and then more screams, men’s screams. And somebody lunged from the crowd and swung at David, and he moved so quickly I was flung away, the blow missing David’s head by a foot.

“No!” David yelled at the man. “We don’t want this.”

Then the man swung again and this time David caught the fist in his huge hand. He jerked the man close. “We’re not doing this,” he hissed and flung him back into the crowd.

David grabbed Tom’s arm again, trying to guide him back toward the building. “This is stupid, don’t be pulled into it.”

Thomas growled and let himself be pulled along, and someone spit in his face, and I saw it, the dead look in his eyes, to be spit on and do nothing. And still David pulled us toward the safety of the building, brushing aside the curses of men whose necks he could snap with the single flex of his arm. And still he did nothing. He did nothing all the way up to the end, when a thin, balding forty-year-old man stepped into his path, raised a gun, and fired point blank into his chest.

* * * *

THE BLAST WAS deafening.

—and that old sadness gone. Replaced by white-hot rage and disbelief, blue eyes wide.

People tried to scatter, but the crush of bodies prevented it. David hung there, in the crush, looking down at his chest. The man fired three more times before David fell.

* * * *

“ASHES TO ASHES, dust to dust. Accept our brother David into your warm embrace.” The priest lowers his hands and closes the bible. The broad casket is lowered into the ground. It is done.

Dr. Michaels carries the boy as my sister helps me back to the limo.

* * * *

THE NIGHT DAVID was killed, after the hospital and the police questions, I drove to the sitter’s to pick up my son. I drove there alone. Mary hugged me and we stood crying in the foyer for a long time.

“What do I tell my two-year old?” I said. “How do I explain this?”

We walked to the front room, and I stood in the doorway. I watched my son like I was seeing him for the first time. He was blocky, like his father, but his bones were longer. He was a gifted child who knew his letters and could already sound out certain words.

And that was our secret, that he was not yet three and already learning to read. And there were thousands more like him—a new generation, the best of two tribes.

Perhaps David’s mistake was that he hadn’t realized there was a war. In any war, there are only certain people who fight it—and a smaller number who understand, truly, why it’s being fought. This was no different.

Fifty thousand years ago, there were two walks of men in the world. There were the people of the ice, and there were the people of the sun.

When the climate warmed, the ice sheets retreated. The broad African desert was beaten back by the rains, and the people of the sun expanded north.

The world was changing then. The European mega-fauna were disappearing. The delicate predator/prey equilibrium slipped out of balance and the world’s most deadly climax predator found his livelihood evaporating in warming air. Without the big herds, there was less food. The big predators gave way to sleeker models that needed fewer calories to survive.

The people of the sun weren’t stronger, or smarter, or better than the people of the ice; Cain didn’t kill his brother, Abel. The people of the North didn’t die out because they weren’t good enough. All that bone and muscle and brain. They died because they were too expensive.

But now the problems are different. The world has changed again. Again there are two kinds of men in the world. But in this new age of plenty, it will not be the economy version of man who wins.

* * * *

THE LIMO DOOR slams shut. The vehicle pulls away from the grave. As we near the cemetery gates, the shouting grows louder. The protestors see us coming.

The police said that David’s murder was a crime of passion. Others said he was a target of opportunity. I don’t know which is true. The truth died with the shooter, when Tom crushed his skull with a single right-hand blow.

The shouting spikes louder as we pass the cemetery gates. The protestors surge forward, and a snowball smashes into the window.

“Stop the car!” I shout.

I fling open the car door. I climb out and walk up to the surprised man. He’s standing there, another snowball already packed in his hands. I’m not sure what I’m going to do as I approach him. I’ve gotten used to the remarks, the small attacks. I’ve gotten used to ignoring them. I’ve gotten used to saying nothing.

I slap him in the face as hard as I can.

He’s too shocked to react at first. I slap him again.

This time he flinches away from me, wanting no part of this. I walk back to my car as the crowd finds its voice. People start screaming at me. I climb back into the limo and they close around me. Hands and faces on the glass. The driver pulls away.

My son looks at me, and it’s not fear in his eyes like I expect; it’s anger. Anger at the crowd. My huge, brilliant son—these people have no idea what they’re doing. They have no idea the storm they’re calling down.

I see a sign held high as we pass the last of the protestors at the gate. They are shouting again, having found the full flower of their outrage. The sign says only one word: Die.

Not this time, I think to myself. Your turn.

Afterword

This story was inspired by my discovery during college that science can not only be wrong, but also biased. During my sophomore year, I had a three-hour gap between classes twice a week, and with nothing better to do, ended up at the campus library where I eventually found my way to the scientific periodicals. The library had issues of various scientific journals dating all the way back to 1906. So that’s where I started, 1906, and I spent the next two years reading my way up to the present. I read every single issue of one prominent scientific journal—nearly a hundred years worth. I’m not sure many people have ever done that. It changed my whole view of science. I learned that science is fallible, and that in the wrong hands, it can absolutely be racist.

I learned that scientists have always had a talent for proving that people who looked and acted just like themselves—who came from backgrounds just like themselves—were the smartest, best kind of people in the world. Don’t believe me? Go to the scientific journals; read the 1920s. You’ll find entire journal issues preoccupied with racial hierarchies; you’ll find several studies dedicated to helping readers perceive the vast universe of significance which can be inferred from racial differences in average cranial capacity that amount to little more than a few dozen ccs. (You don’t even want to see what science did with the US army’s helmet-size data from WWI). But these same scientists who made mountains out of 30cc mole hills are strangely silent on the subject of the Neanderthal—a walk of man whose cranial capacity is actually larger than modern man’s. In some cases, much larger. Another thing I learned about science from reading those periodicals is this: science is very good at ignoring facts which don’t fit the accepted paradigm.

Things are much better now than they used to be. Science is better at weeding out the biases of its practitioners—but you can still sometimes see those preconceptions bleeding through in spots if you look hard enough. I think this has been particularly true in the case of the Homo neanderthalensis. If you went to museums and looked at the old displays, a lot of what you saw, until recently, was just wrong. Recent DNA studies are proving that. What you see in those old museum displays wasn’t really science at all, but an interpretation filtered through a series of faulty presumptions which are indicative—if they are indicative of anything—more of the biases of the scientists who made the model than of any ultimate truth about the Neanderthals themselves. Why put dark hair, dark eyes, and olive skin on a Neanderthal? Yet again and again, that’s what you’ve seen.

Up until about five years ago, when new DNA data started rolling in, I would still see a fair amount of that same old arrogance I remembered from reading the periodicals. I saw scientists displaying a talent for proving that people who look and act just like themselves are the smartest, best kind of people in the word—and our lowly Neanderthal placed a distant second. There is one particular Neanderthal fossil that has always fascinated me beyond all others: Amud I. Amud I was a truly massive individual. He was tall, and not just for a Neanderthal. He was a shade under six feet, and had a cranial capacity of 1740ccs. (Modern Europeans average around 1410.) Until recently, in certain scientific circles, they were still debating if Neanderthals had language! What the hell was Amud I doing with 1740cc’s worth of gray matter, if not speaking? Brain tissue is metabolically expensive. All that muscle, all that bone, it has to be paid for.

What do we really know about Neanderthals? We know what their bones tell us. By the ratios of the carbon isotopes in their bones, we can reconstruct their diets. We can study the marks left by their muscle attachments. We can pour mustard seeds into their skulls and then empty those seeds into graduated cylinders in order to estimate their cranial capacity. So we know this: they had large brains; they had truly massive musculatures not typically found today except in elite athletes. They were hunters of big game. That they are no longer alive isn’t evidence of some intrinsic inferiority.

But there’s a change coming. We’re at a point when some very difficult questions about cloning need to be addressed; and by addressed, I don’t mean just creating more laws against it which most of the world won’t be bound by anyway. It’s not enough to create laws against certain procedures because the truth is that man has proved again and again that when a new technology becomes available, it will be used—somewhere. We’ve cloned dogs, and sheep, and monkeys. At some point in the very near future we’ll clone humans. It will happen. But the bar won’t stop there. That bar will keep moving, and I’m not saying that’s necessarily a bad thing, because it’s what we do, as humans—we keep moving that bar; that’s our specialty. But there are a lot of different ways things can go. And while we’re out there practicing the art of being who and what we are, it might be worth considering what will happen if we bring back something that’s better than us.

Jay Lake

“IT’S A SIMPLE concept, really.”

Grover hated public speaking. Which was ironic, given his job in sales development for Quantum Thermal Systems. A half-empty church basement full of metal folding chairs was a special nightmare. He could hear his voice echoing off the metal half-moons topping each vacant seat, so that there was a metallic ring just a fraction of a beat behind his words. Debris punctuated the scuffed linoleum floor: candy wrappers, folded over flyers, and—improbably enough in the function room of the Second Methodist Church—a torn condom wrapper.

The chairs were mostly empty, the rest populated by a bored collection of farmers, ranchers and small town businessmen. Most were already nodding off, the rest sat in exaggerated poses of doubt, like a particularly truculent line of Hummel figurines. Salt of the earth, his mother would have called these men. Salty old bastards, more like it.

There were no women present this evening.

Grover held up his model. It was built from styrene sheets bought on sale at Hobbytown, glued to a styrofoam core with a few strategic wires dangling out of one end, simply because nobody ever believed in a prototype without exposed copper. The whole thing was spray painted matte black, with a bit of silvery duct tape for added effect. Any engineer knew what a casing was — skin for the reality within, bearing no more relationship to performance than the line of an automobile’s fender did to the drive train.

People, though, regular people who went to work every day and drove pickup trucks and had trouble balancing their checkbooks . . . they needed to see the semblance of a thing before they could understand the reality beneath the skin. Farmers knew their nitrogen from their phosphates, but physical chemistry was as foreign to these people as Russian literature or Indonesian rijsttafel.

Damn it, he thought. His mind was wandering again.

“This little device,” he said, then stopped to clear his throat. Try again. Pale, pasty and too fat to look authoritative, Grover had to rely on the words. He didn’t have the convincing manner of a born salesman like Brody in the San Mateo office, and he’d never mastered the art of dressing his inconveniently round belly to look anything but sloppy-pudgy.

“This little device will save you more trouble and money than you could ever have thought possible.”

He spun the prototype in his hands.

“The production model will weight about twenty pounds. It will cost you about a hundred dollars. It will store about 18,000,000 joules of heat.”

Grover paused, took a deep breath.

“That’s one day of peak thermal output of a cubic yard of fresh horse manure as it begins to compost. The equivalent of almost 800 kilowatt hours of electricity, the energy an average American household uses in a month. All of it with a loss of less than one percent efficiency per month.”

The collective yawn was palpable. Chair legs scraped as some of the men gathered their weight to walk away. But he could see two or three chins tilted, two or three thoughtful looks.

Two or three people who understood what this thing would mean!

“It’s called thermal superconductivity,” Grover told them. The real details were a closely guarded secret, but the idea . . . the idea was priceless. “The future is here in our hands, if you can just imagine what this will do. The world has never seen anything like it. Not since the discovery of fire.”

* * * *

“THIS MATERIAL HAS two states,” said Minnie. “Balanced and gradiated.”

Grover shifted in his chair. The PowerPoints were either overly detailed or mysteriously vague. Or maybe it was just Minnie. He could imagine her hair undone from its bun, floating in wiry curls around that sensuous face.

Who knew Puerto Rican girls were so hot? Especially physical chemists.

“We’ve got the gradiated state working now,” she went on. “It’s in the form of a textile, for ease of manufacture and use. In the near future we’ll have rigid forms with high ductility for applications requiring shaping or specific topologies. Transfer rates aren’t optimal, but even now we can keep up with domestic uses. We’re not far from internal combustion engine temperature ranges.

“As for the balanced state, I can’t tell you much more than to say we expect it to be stable and replicable before the end of the next fiscal quarter.”

As an engineer, he was lost among the sworn-to-NDA money men in the room. Grover’s job was sales development for the product. Minnie’s job was product development itself, and the high level sell of the concept.

And, well, to finish inventing it.

“The gradiated state moves heat. It’s that simple. Flow direction, intensity and maxima are governed by extremely low voltage electrical inputs which realign the channeled carbon nanostructures.”

The room was quiet, with the intensity of a dozen pairs of ears straining toward the biggest payoff in the history of venture capital.

“She means we can turn it off and on,” Grover offered in a quiet voice. He’d taken a few yards of the lab castoffs home to play with, on the Q.T. Sales development, after all. Plus maybe a meaningful prototype, if he could get clearance for that. And it was cool as hell, even if the thermal gradiation was uncontrollably locked into place on the stuff he had. “Like a faucet. Hot, cold, trickle, flood.”

“Right.” Minnie made a face at him, somewhere between sweet and prissy. “That’s very, very useful, but it’s only a form of transference.”

“So . . . ” said one of the money men in a thoughtful voice. “We could remove the car’s radiator, but the block heat still has to go somewhere.”

“Right.” She smiled, warming Grover’s heart. “That’s where the balanced state comes into play. Think of it as a really big sponge, storing that block heat until we want to let it out again.”

That elided a lot of detail, but the real nut and bolts of this process were still burn-before-reading secret.

“What do we do with the heat later?” asked the money man.

“Anything you want,” Grover said. “Heat is power. Power is everything. The entire energy production and consumption system begins to feed itself, increasing our efficiencies dramatically across the society. Hell, this thing could have a net effect on global warming. It’d be nice to have Key West back, huh?”

There was a scatter of nervous laughter. Someone behind him stage whispered, “The Caymans, too. I had money there.”

“Gentlemen,” said Minnie in a tone of voice that made it clear that Grover’s role as a shill was done. “What Quantum Thermal Systems does is all about the money. Saving the world is just a bonus.”

* * * *

GROVER’S IPHONE PRO rang. It took him a minute to disentangle from dreams of fire alarms and swimming pools filled with warm Kool-Aid, but he managed to slap the phone off the table onto his mattress and mash it to his ear.

“Grove, it’s Brody.” The sales manager sounded panicked. “Is that you?”

“Me?” Grover wasn’t sure who else it would be. He was supposed to have been in Cleveland, but Wei Ming had taken that trip because Grover’s allergies were acting up. Still, he never had a house sitter.

Brody’s voice caught. “Take your prototypes and get out. Drive. Away. Borrow someone else’s car.”

“Wha . . . ?”

“The office just got whacked. Dorsey says it was a Blackwater contract job. Whole building’s in flames. Somebody ran Minnie off the road, snatched her, and took everything she had in her vehicle. Wei Ming’s hotel room got tossed in Cleveland, he’s in the ER there beat all to shit. There were two guys trying to break into my place just now, but I got out.”

Shit. Allergy meds or not, Grover was suddenly very, very awake. They’d joked about this around the office, called it the Silkwood Scenario, after that poor woman killed by the nuclear power industry back in the 1970s for blowing the whistle. What if Exxon came gunning for us? What if Con Ed sent out the utility ninjas?

It wasn’t a joke any more.

He scrambled out of bed, dragged himself into sweats, and stumbled down the short hall to his office.

Someone was standing in there, silhouetted in the streetlight glare through the window overlooking Circular Avenue. The figure’s hand came up.

Grover’s next thought arrived with utter clarity. I’m going to die now.

“Get in here,” Minnie hissed.

A hard, nauseating ripple of shock twisted through Grover. “What?”

“I thought you were dead in Cleveland. Then I heard your damned phone ring.”

“Dead? Me?” He tried to grapple with the obvious question. “What the hell are you doing in my house? Brody says—”

“Brody’s working for them.” Her breath heaved, ragged and rough on the edge of collapsing from stress.

“Con Ed?”

She blinked. “What?”

“Sorry, sorry.” He sneezed. “Allergy meds.”

“Shut up.” She picked up a satchel which had been on the floor by his desk. “Let’s go.”

Grover grabbed her arm. “What are you doing here?”

“Looking for that prototype battery you like to haul around. That, and your laptop.”

Something wasn’t adding up yet. Actually, everything wasn’t adding up yet. “Did you find them?”

“Yes. Now let’s go.”

In the other room, his phone began ringing again.

“Minnie, if you believed I was dead in Cleveland, why did you think my laptop would be here?”

The phone rolled to voicemail, then started ringing again a few seconds later.

“Desperate times, Grove.” She slugged him hard, then kicked him in the nuts as he collapsed. “Good luck with your house fire.”

* * * *

HE FOUND HIMSELF on his hands and knees. The damned iPhone was still ringing in the other room, with that digitized jangly 1960s payphone bell he used to think was so funny. Grover smelled smoke.

The alarms weren’t chirping, though.

Painfully, he looked up. His vision was swimming in doubled circles, but that was enough to see that the smoke alarm in his office had been yanked out of the ceiling.

Where’s the fire?

Minnie had left him for dead. He wasn’t walking out of here, that was for sure. Weren’t you supposed to crawl in a fire, anyway?

Grover slid over to the office door and peeked underneath. There was flickering orange light in the hallway. His office window opened onto view of rose bushes and a spike-topped iron fence at the back of the condo complex. Better than being burnt to death, maybe, but not much.

I am going to die now.

He was tired of that thought already. He keeled over onto his side, tried to keep from crying, then wondered why he cared if he cried. His eyes were running freely with the burn from the smoke.

Instead Grover thought about Minnie. What the hell was she doing? Brody had thought she was dead. QTS was gone in a night of murder and flames.

She’d said it was all about the money. Someone must have offered her a ridiculous amount to take the product and disappear.

An amount so ridiculous she’d kill for it?

The phone finally stopped ringing. Smoke was creeping under the door, sending gray fingers up to the ceiling. Grover’s midsection no longer felt like it had gone nova, but he was stuck here. His only hope was that the fire department arrived before the fire did.

No sirens yet.

A thought made him sit upright, which in turn brought an unpleasant rush to his head. She’d been here looking for his dummy prototype. She hadn’t known he’d taken the defective samples home.

“I’m going to live,” Grover told the fire.

He dropped to all fours again and crawled to the closet. It was full of supplies, winter clothes, the sort of crap that a bedroom-turned-office accumulated. He’d tossed his sweaters back in there after dropping out of the Cleveland trip. Underneath them was four yards of strangely slick black cloth, so dark it looked like a hole in the shadows of the closet. Eighteen inches wide, twelve feet long. Enough to wrap himself like a mummy and walk out through the fire.

So long as he got the gradiation right. It would do him no good for the nanostructures to pipe all the heat of the fire inward to his skin.

Power still seemed to be working, even with the fire. Grover tugged his lamp off the desk, switched on the bulb, and set the cloth against it to see which side got hot and which side stayed cool.

* * * *

“YOU CAN’T HOLD me,” Grover said. “And I’m going public as soon as I find a reporter.” Or a phone, at least, he amended.

Special Agent Angela Looks Twice stared him down. “I’m not going to let you walk out that door.” The compact woman from the FBI was currently in the grip of fury. Grover was perfectly willing to believe she could take him apart, joint by joint if required.

They were crowded together in the manager’s office of the Denny’s two blocks away from his condo complex. The complex had gone four alarms last he heard. He and the agent were crammed into a tiny room arranged for the convenience of one person. The manager clearly spent a lot of time trying to motivate low-wage workers through old fashioned intimidation, at least judging by the posters on the wall warning of all the different ways a job could be lost.

“Everyone connected with Quantum Thermal Systems is missing or dead.” She stabbed a finger at him. “Your colleague in Cleveland. Brody. At least four innocent bystanders that we know of. Everyone. Except you.”

“Right.” Grover felt a laugh welling up inside him. He swallowed it hard. “You’re never going to suck this thing down the memory hole now. Hell, I must have spoken to four or five dozen groups in past six months. A lot of investors heard the pitch. Now you’re going to have victim’s families asking questions.”

“You’d be amazed what gets sucked down the memory hole.” Looks Twice had a grim smile on her face. “You walked out of a 1100 degree fire with normal skin and core temps. The defense applications of this thing alone are worth a total blackout.”

“Not to mention the firefighting applications,” Grover said sarcastically. “I don’t care what the hell you do with it. It just can’t stay secret. That’s what all the killing, all the fires are about. Covering it up. Making it go away. Just another failed startup. Except most startups don’t end in a series of murders and kidnappings.”

Looks Twice rubbed her temples, then gave him a long, slow look. “Ever hear of Heaven’s Gate? Cults make great cover for this kind of operation. Everybody spends a minute feeling sorry for the dead whack jobs, then moves on.”

“Got a lot better at it since Karen Silkwood, huh?” Grover stood up. “Arrest me, or let me go.”

Her fists clenched. “I can hold you as a material witness.”

Grover grabbed the doorknob. When had he ever fought back like this? Maybe since people died tonight. “Or you can help me . . . ”

“Don’t open the door, Mr. Ruggles. There are a number of pissed off cops out there who will stop you. They might even check with me, after you’re finished resisting arrest.“

“So, arrest me now or let me go.”

“And you’ll walk out and find a reporter? I can promise you, anyone with the resources to coordinate this many assaults and arsons in one evening will have no trouble finishing the job with respect to you. Any interview you go to will be the last thing you ever do.”

“Then help me stay alive long enough to go public,” Grover said with a growl. He wondered where all this courage was coming from, and how soon it would evaporate. “Go so public it won’t matter. Fuck the NDAs. There’s no one left to sue me for violating them.”

He leaned over her desk, being as persuasive as he knew how. Do it for Brody, he thought. For Wei Ming. For all of them.

“I didn’t invent this stuff, but I can explain it well enough that people with the right training will know what to do to recreate it. If thirty or forty universities and corporate labs nationwide are working on it, there’s not much point in killing to keep the secret. I’ll make the memory hole so damned big that even Karl Rove couldn’t disappear this thing. Hell, once the Chinese or the Russians start working on the knock-offs, the QTS tech will be worldwide. And it will change the world.”

Looks Twice snorted with a rueful amusement. “You don’t think small, do you?”

“Almost all the time,” he admitted. “I’m a small kind of guy. Just not this time. I walked through fire, remember? Think about what else that stuff will do.”

The last remnants of anger seemed to leave Special Agent Looks Twice in a heaving rush. She pulled a business card from her jacket pocket. “You’re free to go, Mr. Ruggles. Call me if you think of anything. I suggest you don’t leave town without talking to the District Attorney.”

Grover was surprised. He’d always figured FBI agents for world class hard asses when it came to law and order. That was pretty much the job description, after all. He gathered up the oversized plastic bag into which someone had stuffed the strips of thermal superconductor. The plastic was bubbled and stretched from residual heat.

“Mr. Ruggles,” Looks Twice said tentatively as he pulled open the door.

Grover turned around, a state wage-and-hour poster looming large in his peripheral vision. “Yes, ma’am?”

“My mother and my baby brother died when our trailer burned. A lot of years ago. I find a . . . special pleasure in investigating arsons.” She took another deep, ragged breath. “If they’d been able to walk through fire . . . ”

“Sometimes it is all about saving the world,” he said.

* * * *

GROVER WAS ON local television the next morning. The reporter loaned him her cell phone as he left the studio, and promised to give out the number to everyone she could think of who might be interested.

Within an hour, driving a rented Focus hybrid along a random set of roads through the Willamette Valley, he took calls from reporters from the San Jose Mercury News, the New York Times and Agence France-Presse. He couldn’t do anything about the cell phone being traced except to keep moving.

Around noon he stopped at the public library in Silverton, then went by the local post office to mail samples of the thermal superconducting cloth to every major university he could think of. First class, no tracking, paid for in cash. That was as anonymous as he could think to make the process of getting the stuff out into the world.

After mailing off the samples, he drove east into the Cascades. One of the Mercury News reporters called back with home number of a science fiction author who was also an “A” list blogger and a feature writer for Wired. Grover called and told his story. The writer immediately grasped the implications of the idea, in both states — gradiated and balanced. “Waste heat alone,” he said. “You’re on the way to providing a manageable approach to global warming, and closing a huge portion of the loop on power generation. Those are two of the biggest stumbling blocks on the Kardashev scale.”

“It’s still lossy,” Grover said, guessing at what the other man was talking about. “We can’t escape the Laws of Thermodynamics.”

“Right, but you’re going from maybe thirty percent thermal efficiency on internal combustion to, what, ninety-five percent? Or more. You just keep reusing it.” The writer sounded thrilled. “It’s the future by degrees. This has applications everywhere. Did you know that they put air conditioners in equipment shacks in North Slope Alaska? Forty below outside, and a compressor running inside the insulation to manage the heat rise. This stuff . . .”

The conversation spun off into space exploration, medicine, environmental remediation, the potential for home-based power generation from waste heat, before the mountains ate the cell phone signal. Grover laughed at the waste heat idea, thinking back on his manure pile analogy.

* * * *

THE SILKWOOD SQUAD caught up with him just on the eastern side of Santiam Pass. Grover was surprised to have gotten even that far.

A helicopter with no markings, not even a tail number, was parked on the highway. He could see a large yellow dump truck at a curve half a mile downhill. They were roadblocking any potential witnesses.

Minnie stood in front of the helicopter, wrapped in an oversized windbreaker. Somehow she didn’t seem so beautiful to him any more. There were three men with her. They were bulky, in gray suits and dark glasses. It was a scene straight out of Central Casting. Grover found the sheer lack of imagination offensive.

He pulled the car over and got out. “It’s a rental,” he shouted, feeling light-headed. Minnie’s fire had finally caught up to him. “Probably don’t need to blow it up.”

Minnie nodded. “We tracked you by the car company’s GPS.”

“The secret is blown.” Grover took a couple of steps toward Minnie. “It’s all over the world now. Not the sales hokum we’ve been passing this whole time. The real thing, as much as I had of it. Including samples.” His knees quivered. “You can shoot me now, like you did Brody and Wei Ming, but it doesn’t matter any more.”

“Hmm.” She flicked her hand and the big men came for Grover.

“I saved the world,” he shouted just before the first blow landed hard enough to crack his jaw.

Minnie’s voice was distinct over the grinding thump of brass knuckles and tape-wrapped pipes. “And you pissed away a hell of a lot of money doing it.”

* * * *

THE BIGGEST SURPRISE was that they let him live. A long haul trucker had found Grover by the side of the road, and called in the EMTs, who’d evacuated him by helicopter. Now he sat in a Salem hospital, aching at every joint. His right eye had a detached retina and his left was full of blood.

Something moved in the doorway. Grover squinted, mumbling, “Who’s there?”

“Special Agent Looks Twice,” said the blur.

“Oh, hey.” At least, that’s what Grover tried to say.

“Don’t talk. I just thought I’d tell you there’s no air traffic control record on a helicopter near the Santiam Pass. No one saw anything coming and going. So far as the Jefferson County sheriff’s department is concerned, you drove up there alone and tried to commit suicide.”

“Beat myself to death?”

“I believe the press was told you’d thrown yourself off the top of a road cut and sustained injuries striking the cliff on the way down.” She stood close enough to the bed that he could see her.

Grover fought to make the next words clear. “And the thermal cloth?”

“Front page news, pretty much everywhere.” He thought she might have smiled. “You won.”

“Heat is the engine of the world.” He knew that wouldn’t make sense to her, not through his shattered mouth.

“Right. I’ve got to go.” Looks Twice stroked his arm briefly. “Hey, firewalker. They ever let you out of here, give me a call sometime.”

Grover lay back, imagining what the future might be like.

Afterword

I’ve been fascinated by thermal superconductivity for years. Waste heat management is one of the key issues facing a civilization progressing along the Kardashev scale, so thermal superconductivity would be as profound a breakthrough as the control of fire, or possibly electricity. I’ve used thermal superconductivity as a minor world-building element in various stories, but never addressed the concept in detail before this story. Seeds of Change looked like the perfect opportunity to tackle the topic directly, given that such a concept would be just about the most profound revolution ever seen in technology. Think about how much of the design of any electronic device is concerned with waste heat management. Likewise internal combustion engines. Or the heat transfer issues in climate control within residences and commercial buildings. The list is endless.

It was challenging getting the science in the story right, even in this case, where the science is “rubber science” because rubber science still has to make sense. If I knew how thermal superconductivity could work, I’d be a billionaire instantly. But I have to sound like I know how to make thermal superconductivity work. That means getting it right with all the ordinary science which is packed around the rubber, and it means getting the rubber to sound legit. Mostly I had to get the thermal and energy science stuff right. I have a friend who’s a power systems engineer who helped with that, and there was a very involved discussion on my LiveJournal about the thermal characteristics of manure. That concerned one line in the story, but a lot of the rest of what I needed flowed out of that conversation as well.

To me, the theme of Seeds of Change is about what it would take to fundamentally shift the world. Most of the change we experience is incremental—a better search engine algorithm, a new flavor of Ben & Jerry’s. Even the larger changes—hybrid cars, for example—are mostly larger increments. Truly socially disruptive changes are quite rare: I’m thinking on the order of fire, agriculture, structured legal codes, open water navigation, gunpowder, engines, electricity. This lead me to ask: “What would move the world so profoundly again?” I can think of a few things: the arrival of an extraterrestrial species on Earth, functional immortality, micropower generation (which is implied in my story), thermal superconductivity. Of those, alien landings and immortality didn’t meet the “feel” of the theme. So I went with thermal superconductivity, which has fascinated me for years. I wish someone would invent this darned stuff. It would be mighty cool.

K.D. Wentworth

JOE SETTLED INTO his accustomed seat before the Brass Tack’s polished black granite bar. It had been a tough day, full of stupid meetings. But, hey, lots of days were tough. Nothing new there. The jukebox was grinding out something unmelodic and off to one side, a frizzy-headed woman regarded the beer bottle in the middle of her table with dread as though it was about to explode. Outside, the July sun was blazing, even at 5:30 a force with which to be reckoned.

“Cold one?” Tom Whitebear, the barkeep asked. He was tall, black-haired, and laconic with the presence of a deep dark well, absorbing his patrons’ words and giving back blessed silence.

Joe nodded, liking that he didn’t even have to ask. His tongue was already full of holes from biting it all day long. If Salinger emailed him one more time demanding reports that weren’t even due yet, by God, he would take a stapler to the idiot’s balding head.

Tom slid a bottle with a strange blue and gold label in front of him and stared at it morosely.

“I drink Miller,” Joe said, too weary to raise his voice.

“This is Miller,” Tom said, sliding a slip of paper across the gleaming blackness. “The packaging’s just different. They call it a ‘Smart Bottle.’ Even comes with its own instructions.”

“Instructions for a freaking bottle of beer?” Joe blinked.

Tom seized a cloth and buffed the bar as though it was smeared—which it wasn’t. “You been in Tibet or something? Press has been screaming about this for weeks. It’s the law, went into effect today. Brew’s only available in these fancy ‘Smart’ bottles now. Supposed to save the environment. Big Brother watching out for us and all that.”

“I don’t get it.” Joe flicked the back of his finger against the cold glass, making it ring. The label featured a man holding up a bottle and smiling broadly.

“Whole damn country, no, make that the whole damned world, is going to hell.” Tom peeled off a tab below the label that ran all around the bottle and pushed it gingerly toward him with his fingertips. “Joe Browder, meet your Smart Bottle,” he said in an oddly formal way, as though he were introducing Joe to a potential partner at a stupid speed-dating party.

Joe noticed belatedly that the barkeep was pulling off latex gloves. “What the hell?”

“Hope the two of you will be very happy,” Tom muttered and slouched off to wait on a man at the far end of the bar.

Joe picked the bottle up, finding the label’s texture oddly rough. His hand tingled and he set the bottle aside to examine his palm. The skin was slightly reddened as though he’d scraped it against something.

“Greetings!” a hollow little voice said. “I am your Symesco A2300 Smart Bottle equipped with DNA recognition software and a high environmental consciousness quotient. I will be handling all your future beer consumption needs.”

Joe pushed back off the stool, his heart thumping. “Did that thing just talk?”

“Drink me, Joe,” the bottle said, “while I’m nice and frosty. Delay will not improve the esthetics of the experience.”

Hairs crawled on the back of his neck. “Like hell I will!”

“Might as well,” Tom said as he came back. “Once you touch the sensor, infernal thing is imprinted on you. It’s yours—permanently.”

Fuming, Joe threw a five on the bar and stood.

“Actually, it costs twenty-five bucks.” Tom pushed it toward him. “One-time deposit. And you take it with you so I can refill it the next time you come in.”

Joe pulled a twenty out of his billfold and added it to the five, glaring at the offending bottle with its ridiculous blue and gold label. “Not in this lifetime, buddy!” He turned to go.

“I wouldn’t do that if I were you,” Tom said to his back. “Damn thing has a proximity sensor.”

Joe was halfway to the door when the racket began, sort of like a tornado siren augmented by the agonies of a dying cat. The closer he got to the door, the louder it became. The other patrons were holding their hands over their ears and appeared to be shouting at him, but he couldn’t hear them. Tom seized the bottle and followed him to the door. “You got to take it with you,” he said, “or it won’t let up!”

Joe snatched the bottle and the moment he touched it, the clamor cut off. At a side table, a man and woman, both in their twenties, shook their heads. “Dumb-ass,” the man, who looked like one of those fresh-faced business school grads, said. “Didn’t read the instructions, did you?”

Joe had a half a mind to break the bottle over the sod’s head. Tom retrieved the abandoned operating sheet and pushed it into Joe’s other hand. “You need to familiarize yourself with the bad news,” he said in a low voice. “I’m afraid things are going to be very different around here.”

Joe stuffed the paper into his pocket and stalked out.

* * * *

JOE POURED OUT the bottle on the sidewalk and drove his Mazda home to his apartment. Terri was waiting with lasagna in the oven. She worked as a third grade teacher so she arrived home first. Unfortunately, she always wanted to natter at him about how exhausting her day had been the second he got home, so that he never had a quiet moment to put his thoughts in order.

“What’s that?” she said as he closed the door.

“Something called a ‘Smart Bottle,’ ” he said, setting it down with a thump on the breakfast bar. He dropped his briefcase onto the coffee table and wrenched at his tie. “The bartender tricked me into buying it at the Brass Tack.”

“My class read about these,” she said, picking it up and turning it under the light to examine the label. “They’re supposed to cut down on the need to recycle.”

“Actually, Symesco Smart Bottles cannot be recycled,” the hollow little voice said. “We are engineered with DNA recognition software to provide years of imbibing pleasure.”

Joe sank onto the couch. “I can’t get the stupid thing to shut up.”

“Why do you have DNA recognition capabilities?” Terri said.

“I am Joe’s bottle,” it said. “If I could not recognize him, I might be employed by any number of unauthorized users. That would be unhygienic.”

“Correction,” Joe said, taking the bottle out of Terri’s hand. “You were my bottle. Now you’re just so much scrap glass.” He opened the pantry and tossed the bottle with a clank into the recycling bin.

The racket began again, this time much worse in the confined space of the apartment. Cursing, he pulled the bottle out. “Stop that!” The wail cut off.

Terri glared. “Did you pay good money for that thing?”

“Washington evidently passed some sort of stupid law when no one was paying attention,“ he muttered, then dug in his pocket for the wadded instructions. “But there must be a way to turn it off, otherwise, you’d have to take it to work with you and even in the shower.”

“Congratulations on your purchase of a Symesco A2300 Smart Bottle,” the instructions read, “The first monumental step toward maintaining a waste-free environment!”

He skimmed down through more bombastic, self-aggrandizing rhetoric, which included the instructions for removing the tab over the sensor and introducing the “client” to the bottle, until he reached “Temporary Deactivation.”

“You can command your bottle to ‘sleep’ when not in use for twenty-four hours at a time,” the instructions read. “with one two-week deactivation permitted every four months when the client wishes to vacation without his Smart Bottle, though this is not recommended. It can be reactivated at any time by simply touching the DNA-sensitive label. Deactivation for longer or more frequent periods will require a waiver from Symesco. Those wishing to apply for the necessary code phrases should call the Symesco Help Line at 1-800-SMT-BOTL or consult our convenient website: www.symesco.com.”

Joe held the brown bottle up. “Sleep, dammit!”

It didn’t seem any different, but this time, when he tossed it into the recycling bin, it didn’t protest.

Terri took the instructions and sat reading them until dinner was ready. They both ate in blessed silence.

* * * *

WHEN HE SHOWED up at the Brass Tack the next day after work, Tom gave him a leery look. “Dude, where’s your bottle?”

“In the recycling bin, where the damn thing belongs.” Joe slid onto a stool and turned his palms down on the blessedly cool surface. “Bring me a cold one.”

Tom folded his white bar cloth. “Can’t.”

“Are you trying to be funny?” Joe asked. “Because it’s been a long frustrating day and I am in no way in the mood.”

“It’s against the law to serve registered Symesco users without their bottles,” the barkeep said morosely. “You’re at least the twentieth person I’ve had to tell that to since noon. Can’t nobody read instructions, I guess.” He polished a bit of imaginary grime.

“And you registered me yesterday,” Joe said. “Gee, thanks.”

“It’s the—”

“—law,” Joe finished for him. “Okay, then sell me another stupid Smart Bottle.” Though the thought of being responsible for two of the infernal devices was sobering, not the sensation he was seeking at the moment.

Tom shook his head. “One to a customer. It’s the—“

Joe shoved away from the bar, knocking the stool over. “Guess I’ll just take my business elsewhere!”

“Won’t do no good,” Tom said, studying his cleaning cloth. “No bar will serve you without checking identification, and you’re in the system now as a Symesco user.” He raised his head and met Joe’s eyes. “Just go home and get your bottle and I’ll refill the blasted thing until your eyes float.”

But he didn’t have time for that. Terri would have dinner on the table in thirty minutes and she would complain all night if he was late. “Forget it!” he said and plunged back outside into the glaring afternoon sun.

He stopped by the Pay-N-Git convenience store on the way home to pick up a six pack. The cooler was almost empty and he had to settle for an off-brand he’d never heard of, Bjorn’s Mountain Gold. Probably tasted like yeast water.

The bored clerk, a narrow-eyed girl chomping on a wad of gum, gave him a stern look from behind the high counter. “ID?”

At thirty-seven, he hadn’t been IDed for at least ten years, maybe more. He blinked. “You’ve got to be kidding.”

“No, sir.” She popped her gum and then jerked her chin to indicate the line of impatient customers behind him. “We never kid. It’s like totally against company policy.”