Книга: Blood Follows

THE BELLS PEALED ACROSS THE LAMENTABLE CITY OF Moll, clamouring along the crooked, narrow alleys, buffeting the dawn-risers hurriedly laying out their wares in the market rounds. The bells pealed, tumbling over the grimy cobblestones, down to the wharfs and out over the bay’s choppy, gray waves. Shrill iron, the bells pealed with the voice of hysteria.

The terrible, endless sound echoed deep inside the slate-covered barrows that humped the streets, tilted the houses and cramped the alleyways in every quarter of Moll. Barrows older than the Lamentable City itself, each long ago riven through and tunnelled in fruitless search for plunder, each now remaining like a pock, the scarring of some ancient plague. The bells reached through to the scattered, broken bones bedded down in hollowed-out logs, amidst rotted furs and stone tools and weapons, bone and shell beads and jewellery, the huddled forms of hunting dogs, the occasional horse with its head removed and placed at its master’s feet, the skull with the spike-hole gaping between the left eye and ear. Echoing among the dead, bestirring the shades in their centuries-long slumber.

A few of these dread shades rose in answer to that call, and in the darkness moments before dawn they’d lifted themselves clear of the slate and earth and potsherds, scenting the presence of... someone, something. They’d then returned to their dark abodes—and for those who saw them, for those who knew something of shades, their departure seemed more like flight.

In Temple Round, as the sun edged higher over the hills inland, the saving wells, fountains and bowl-stones overflowed with coin: silver and gold glinting among the beds of copper. Already crowds gathered outside the high-walled sanctuaries of Burn—relieved and safe under the steamy morning light—there to appease the passing over of sudden death, and to thank the Sleeping Goddess, who slept still. And many a manservant was seen exiting the side-postern of Hood’s Temple, for the rich were ever wont to bribe away the Lord of Death, so that they might awaken to yet another day, gentled of spirit in their soft beds.

It was the monks of the Queen of Dreams for whom the night just past was cause for mourning, with clanging dirge of iron, civilisation’s scarred, midnight face. For that face had a name, and it was Murder. And so the bells rang on, a shroud of fell sound descending upon the port of Moll, a sound cold and harsh that none could escape....

... while in an alley behind a small estate on Low Merchant Way, a diviner of the Deck of Dragons noisily emptied his breakfast of pomegranates, bread, prunes and watered wine, surrounded by a ring of dogs patiently awaiting theirs.

THE DOOR SLAMMED BEHIND EMANCIPOR REESE, RATtling the flimsy drop-latch a moment before sagging back down on its worn leather hinges. He stared at the narrow, musty hallway in front of him. The niche set waist-high on the wall to his right was lit with a lone tallow candle, revealing water stains and cracked plaster and the tiny stone altar of Sister Soliel, heaped with wilted flower heads. On the back wall at the far end, six paces from where he stood, where the passage opened on both sides, hung a black-iron broadsword—cross-hilted and bronze-pommeled, most likely rusted into its verdigrised scabbard. Emancipor’s lined, sun-scoured face fell, becoming heavy around his eyes as he gazed on the weapon of his youth. He felt every one of his five, maybe six decades.

His wife had gone silent in the kitchen, halfway through heating the wet sand, the morning’s porridge pot and the plates on the wood counter at her side still awaiting cleansing; and he could see her in his mind, motionless and massive and breathing her short, shallow, increasingly nervous breaths.

“Is that you, Mancy?”

He hesitated. He could do it, right now—back outside, out into the streets—he knew how to sound depths, he knew knots—all kinds of knots. He could stand a pitching deck. He could leave this damned wart of a city, leave her and the squalling, simpering brats they’d begetted. He could... escape. Emancipor sighed. “Yes, dear.”

Her voice pitched higher. “Why aren’t you at work?”

He drew a deep breath. “I am now...” he paused, then finished with loud, distinct articulation: “unemployed.”

“What did you say?”

“Unemployed.”

“Fired? You’ve been fired? You incompetent, stupid—”

“The bells!” he screamed. “The bells! Can’t you hear the bells?”

Silence in the kitchen, then: “The Sisters have mercy! You idiot! Why aren’t you finding work? Get a new job—if you think you can laze around here, seeing our children tossed from their schooling—”

Emancipor sighed. Dear Subly, ever so practical. “I’m on my way, dear.”

“Just come back with a job. A good job. The future of our children—”

He slammed the door behind him, and stared out on the street. The bells kept ringing. The air was growing hot, smelling of raw sewage, rotting shellfish, and human and animal sweat. Subly had come close to selling her soul for the tired old house behind him. For the neighbourhood, rather. As far as he could tell, it stank no different from all the other neighbourhoods they’d lived in. Saving perhaps that there was a greater variety among the vegetables rotting in the gutters. “Positioning, Mancy. It’s all in positioning.”

Across the way Sturge Weaver waddled about the front of his shop, unlocking and folding back the shutters, casting nosy, knowing glances his way over the humped barrow mound that bulged the street between their houses. The lingering fart heard it all. Don’t matter. Subly’ll be finished with the pot and plates in record time, now. Then she’ll be out, gums flapping and her eyes wide as she fishes shallow waters for sympathy, and whatnot.

It was true enough that he’d need a new job before the day’s end, or all the respect he’d earned over the last six months would disappear faster than a candle-flame in a hurricane; and that grim label—“Mancy the Luckless”—would return, the ghost of old in step with his shadow, and neighbours like Sturge Weaver making warding signs whenever their paths crossed.

A new job. It was all that mattered, now. Never mind that some madman stalked the city every night since the season’s turning, never mind that horribly mutilated bodies were turning up every morning—citizens of Lamentable Moll, their eyes blank (when there were eyes) and their faces twisted in a rictus of terror—and their bodies—all those missing parts—Emancipor shivered. Never mind that Master Baltro wouldn’t need a coachman ever again, except for the grave-digger’s bent, white-faced crew and that one last journey to the pit of his ancestors, closing forever the line of his blood.

Emancipor shook himself. If not for the grisly in-between, he almost envied the merchant’s final trip. At least it’d bring silence—not Subly, of course, but the bells. The damned, endless, shrill, nagging bells...

“GO FIND THE MONK ON THE END OF THAT ROPE and wring his neck.”

The corporal blinked at his sergeant, shifted uneasily under the death-detail’s attire of blue-stained bronze ringed hauberk, lobster-tailed bowl helm, and the heavy leather-padded shoulder-guards. Damn, the lad’s bloody well swimming in all that armour. Not quite succeeding at impressing the onlookers—the short sword at his belt’s still wax-sealed in the scabbard, for Hood’s sake. Guld turned away. “Now, son.”

He listened to the lad’s footsteps recede behind him, and glumly watched his detachment enforcing the cordon around the body and the old barrow pit it laid in, keeping at a distance the gawkers and stray dogs, kicking at pigeons and seagulls and otherwise letting what was left of the dead man lie in peace under the fragment of roof-thatch some merciful passerby had thrown over it.

He saw the diviner stumble ash-faced from the other alley. The king’s court magus wasn’t a man of the streets, but the cloth at the knees of his white pantaloons now showed intimate familiarity with the grimy, greasy cobblestones.

Guld had little respect for coddled mages. Too remote from human affairs, bookish and naive and slow to grow up. Ophan was nearing sixty, but he had the face of a toddler. Alchemy at work, of course. In vanity’s name, no less.

“Stul Ophan,” Guld called, catching the man’s watery eyes. “You finished your reading, then?” An insensitive question, but they were the kind Guld most liked to ask.

The rotund magus approached. “I did,” he said thickly, licking his bluish lips.

A cold art, divining the Deck in the wake of murder. “And?”

“Not a demon, not a Sekull, not a Jhorligg. A man.”

Sergeant Guld scowled, adjusting his helmet where the woollen inside trim had rubbed raw his forehead. “We know that. The last street diviner told us that. For this the King grants you a tower in his keep?”

Stul Ophan’s face darkened. “Was the King’s command that brought me here,” he snapped. “I’m a court mage. My divinations are of a more...” he faltered momentarily, “of a more bureaucratic nature. This raw and bloody murder business isn’t my speciality, is it?”

Guld’s scowl deepened. “You divine by the Deck to tally numbers? That’s a new one on me, Magus.”

“Don’t be a fool. What I meant was, my sorceries are in an administrative theme. Affairs of the realm, and such.” Stul Ophan looked about, his round shoulders hunching and a shudder taking him as his gaze found the covered body. “This... this is foulest sorcery, the workings of a madman—”

“Wait,” Guld interjected. “The killer’s a sorceror?”

Stul nodded, his lips twitching. “Powerful in the necromantic arts, skilled in cloaking his trail. Even the rats saw nothing—nothing that stayed in their brains, anyway—”

The rats. Reading their minds has become an art in Moll, with loot-hungry warlocks training the damn things and sending them under the streets, into the old barrows, down among the bones of a people so far dead as to be nameless in the city’s memory. The thought soothed him somewhat. There was truth in the world after all, when mages and rats saw so closely eye to eye. And thank Hood for the rat-hunters, the fearless bastards will spit at a warlock’s feet if that spit was the last water on earth.

“The pigeons?” he asked innocently.

“Sleep at night,” Stul said, throwing Guld a disgusted look. “I only go so far. Rats, fine. Pigeons...” He shook his head, cleared his throat and looked for a spitoon. Finding none—naturally—he turned and spat on the cobbles. “Anyway, the killer’s found a taste for nobility—”

Guld snorted. “That’s a long stretch, Magus. A distant cousin of a distant cousin. A middling cloth merchant with no heirs—”

“Close enough. The King wants results.” Stul Ophan observed the sergeant with an expression trying for contempt. “Your reputation’s at stake, Guld.”

“Reputation?” Guld’s laugh was bitter. He turned away, dismissing the mage for the moment. Reputation? My head’s on the pinch-block, and the grey man’s stacking his stones. The noble families are scared. They’re gnawing the King’s wrinkled feet in between the sycophantic kissing. Eleven nights, eleven victims. No witnesses. The whole city’s terrified—things could get out of hand. I need to find the bastard—I need him writhing on the spikes at Palace Gate.... A sorceror, that’s new—I’ve got my clue, finally. He looked down at the merchant’s covered body. These dead don’t talk. That should’ve told me something. And the street diviners, so strangely terse and nervous. A mage, powerful enough to scare the average practitioner into silence. And worse yet, a necromancer—someone who knows how to silence souls, or send them off to Hood before the steam leaves the blood.

Stul Ophan cleared his throat a second time. “Well,” he said, “I’ll see you tomorrow morning, then.”

Guld winced, then shook himself. “He’ll make a mistake—you’re certain the killer’s a man?”

“Reasonably.”

Guld’s eyes fixed on the mage, making Stul Ophan take a step back. “Reasonably? What does that mean?”

“Well, uh, it has the feel of a man, though there’s something odd about it. I simply assumed he made some effort to disguise that—some simple cantrips and the like—”

“Poorly done? Does that fit with a mage who can silence souls and wipe clean the brains of rats?”

Stul Ophan frowned. “Well, uh, no, that doesn’t make much sense—”

“Think some more on it, Magus,” Guld ordered, and though only a sergeant of the City Watch, the command was answered with a swift nod.

Then the magus asked, “What do I tell the king?”

Guld hitched his thumbs into his sword-belt. It’d been years since he’d last drawn the weapon, but he’d dearly welcome the chance to do so now. He studied the crowd, the tide of faces pushing the ring of guards into an ever tighter circle. Could be any one of them. That wheezing beggar with the hanging mouth. Those two rat-hunters. That old woman with all the dolls at her belt—some kind of witch, seen her before, at every scene of these murders, and now she’s eager to start on the next doll, the eleventh—questioned her six mornings back. Then again, she’s got enough hair on her chin to be mistaken for a man. Or maybe that dark-faced stranger—armour under his fine cloak, well-made weapon at his belt—a foreigner for certain, since nobody around here uses single-edged scimitars. So, could be any one of them, come to study his handiwork by day’s light, come to gloat over the city’s most experienced guardsman in these sort of crimes. “Tell His Majesty that I now have a list of suspects.”

Stul Ophan made a sound in his throat that might have been disbelief.

Guld continued drily, “And inform King Seljure that I found his court mage passably helpful, although I have many more questions for him, for which I anticipate the mage’s fullest devotion of energies in answering my inquiries.”

“Of course,” Stul Ophan rasped. “At your behest, Sergeant, by the King’s command.” He wheeled and walked off to his awaiting carriage.

The sergeant sighed. A list of suspects. How many mages in Lamentable Moll? A hundred? Two hundred? How many real Talents among them? How many coming and going from the trader ships? Is the killer a foreigner, or has someone local turned bad? There are delvings in high sorcery that can twist even the calmest mind. Or has a shade broken free, climbed out nasty and miserable from some battered barrow—any recent deep construction lately? Better check with the Flatteners. Shades? Not their style, though—

The bells clanged wildly, then fell silent. Guld frowned, then recalled his order to the young corporal. Oh damn, did that lad take me literally?

THE MORNING SMOKE FROM THE BREAKFAST HEARTH, reeking of fish, filled the cramped but mostly empty front room of Savory Bar. Emancipor sat at the lone round table near the back in the company of Kreege and Dully, who kept the pitchers coming as the hours rolled into afternoon. Emancipor’s usual disgust with the two wharf rats diminished steadily with each refilled tankard of foamy ale. He’d even begun to follow their conversation.

“Seljure’s always been wobbly on the throne,” Dully was saying, scratching at his barrel-like chest under the salt-stained jerkin, “ever since Stygg fell to the Jheck and he balked at invading. Now we’ve got a horde of savages just the other side of the strait and all Seljure does is bleat empty threats.” He found a louse and held it up for examination a moment before popping it into his mouth.

“Savages ain’t quite on the mark,” Kreege objected in a slow drawl, rubbing at the stubble covering his heavy jaw. His small, dark eyes narrowed. “It’s a complicated horde, them Jheck. You’ve got a pantheon chock-full of spirits and demons and the like—and the War Chief answers to the Elders in everything but the lay of battle. Now, he might well be something special, what with all his successes—after all, Stygg fell in the span of a day and a night, and Hood knows what magery he’s got all on his own—but if the Elders—”

“Ain’t interested in that,” Dully cut in, waving a grease-stained hand as if shooing dock flies. “Just be glad them Jheck can’t row a straight course in the Lees. I heard they burned the Stygg galleys in the harbours—if that bit of thick-headed stupidity don’t cost the War Chief his hat of feathers, then those Elders ain’t got the brains of a sea urchin. That’s all I’m saying. It’s Seljure who’s wobbly enough to turn Lamentable Moll into easy pickings.”

“It’s the nobles that’s shackled the city,” Kreege insisted, “and Seljure with it. And it don’t help that his only heir’s a sex-starved wanton lass determined to bed every pureblood nobleman in Moll. And then there’s the priesthoods—they ain’t helping things neither with all their proclamations of doom and all that tripe. So that’s the problem, and it’s not just Lamentable Moll’s. It’s every city the world over. Inbred ruling families and moaning priests—a classic case of divided power squabbling and sniping over the spoils of the common folk, with us mules stumbling under the yoke.”

Dully grumbled, “A king with some spine is what we need, that’s all.”

“That’s what they said in Korel when that puffed up Captain, Mad Hilt, usurped the throne, though pretty soon no one was saying nothing about nothing, since they were all dead or worse.”

“Exception proves the rule—”

“Not in politics, it don’t.”

The two old men scowled at each other, then Dully nudged Kreege and said to Emancipor, “So, Mancy, looking for work again, eh?” Both dockmen grinned. “Had yourself a run of Lad’s Luck with your employers, it seems. Lady fend the poor sod fool enough to take you on—not that you ain’t reliable, of course.”

Kreege’s grin broadened, further displaying his uneven, rotting teeth. “Maybe Hood’s made you his Herald,” he said. “Ever thought of that? It happens, you know. Not many diviners cracking the Deck these days, meaning there’s no way to tell, really. The Lord of Death picks his own, don’t he, and there ain’t a damned thing to be done for it.”

“Kreege’s made a point there, he has,” Dully said. “How did your first employer go? Drowned in bed, I heard. Lungs full of water and a hand print over the mouth. Hood’s Breath, what a way to go—”

Emancipor grunted, staring down at his tankard. “Sergeant Guld nailed the truth down, Kreege. ’Twas assassination. Luksor was playing the wrong game with the wrong people. Guld found the killer quick enough, and the bastard slid on his hook for days before spillin’ the hand at the other end of his strings.” He drank deep, in Luksor’s cursed name.

Dully leaned forward, his bloodshot eyes glittering. “But what about the next one, Mancy? The cutter said his heart exploded. Imagine that, and him being young enough to be your son, too.”

“And fat enough to tip a carriage if he didn’t sit in the middle,” Emancipor growled back. “I should know—I used to wedge him in and out. Your life’s what you make it, I always say.” He downed the last of his ale, in the name of poor fat Septryl.

“And now Merchant Baltro,” Kreege said. “Someone took his guts, I heard, and his tongue so the questioners couldn’t make the spirit talk. Word is, the King’s own magus was down there, sniffing around Guld’s heels.”

His head swimming, Emancipor looked up and blinked at Kreege. “The King’s own? Really?”

Dully asked, his eyebrows lifting, “Not nervous now, are you?”

“Baltro was of the blood,” Kreege said. He shivered. “What was done between his legs—”

“Shut up,” Emancipor snapped. “He was a good man in his way. It don’t fair the wind to spit in the sea, remember that.”

“Another round?” Dully asked by way of mollification.

Emancipor scowled. “Where d’you get alla coin, anyway?”

Dully smiled, picking at his teeth. “Disposing the bodies,” he explained, pausing to belch. “No souls, right? No trails of where they went, either. Like they was never there in the first place. So, just meat, the priests keep saying. No rites, no honouring, don’t matter what the family’s paid for beforehand, neither. Them priests won’t touch them bodies, plain and simple.”

“It’s our job,” Kreege said, “taking ’em out to the strand.” He clacked his teeth. “Keeping the crabs fat, and tasty.”

Emancipor stared. “You’re trapping the crabs! Selling them!”

“Why not? Ain’t taste any different now, do they? Three emolls to the pound—we been doing all right.”

“That’s... horrible.”

“That’s business,” Dully said. “And you’re drinking on the coin, Mancy.”

“Ain’t you just,” Kreege added.

Emancipor rubbed at his face, which was getting numb. “Yeah, well, I’m in mourning.”

“Hey!” Dully said, straightening. “I seen a posting in the square. Someone looking for a manservant. If you can walk straight, you might want to head down there.”

“Wait—” Kreege began with troubled look, but Dully jabbed his elbow into the man’s side.

“It’s an idea,” Dully resumed. “That wife of yours don’t like you unemployed, does she? Don’t mean to pry, of course. Just being helpful, is all.”

“On the centre post?”

“Yeah.”

Hood’s Breath, I’m an object of pity to these two crabmongers. “A manservant, eh?” He frowned. Driving carriages was good work. He liked horses better than most people. Manservant though—that meant bowing and scraping all day long. Even so... “Pour me another, in Baltro’s name, then I’ll head down for a look.”

Dully grinned. “That’s the spirit... uh...” his face reddened. “No reflection on Baltro’s, of course.”

THE WALK DOWN TO FISHMONGER’S ROUND TOLD him he’d drunk too much ale. He saw enough straight lines, but had trouble following them. By the time he reached the round, the world was swirling all around him, and when he closed his eyes it was as if his mind was endlessly falling down a dark tunnel. And somewhere in the depths waited Subly—who’d always said she’d follow him through Hood’s gate if his dying left her in debt or otherwise put-upon—he could almost hear her down there, giving the demons an earful. Cursing under his breath, he vowed to keep his eyes open. “Can’t die,” he muttered. “Besides, it’s jus the drink, is all. Not dying, not falling, not yet—a man needs a job, needs the coin, he’s got ’sponsibilities.”

The sun had nearly set, emptying the round as the hawkers and net-menders closed up their stalls, and the pigeons and seagulls walked unmolested through the day’s rubbish. Even Emancipor, leaning against a wall at the edge of the round, could sense the nervous haste among the fishmongers—darkness in Lamentable Moll had found a new terror, and no one was inclined to tarry in the lengthening shadows. He wondered at his own absence of fear. The courage of ale, no doubt; that and Hood’s tread having already come so near to his own life’s path somehow convinced him that nothing ill would claim him this night. “Of course,” he mumbled, “if I get the job then all bets are off. And, I gotta keep them eyes open, I do.”

A city guardsman watched Emancipor weave and stumble his way to the reading post in the round’s centre, near the Fountain of Beru, its trickling beard of briny froth splashing desultorily into a feather-clogged pool. Emancipor waved dismissively at the stone-faced guardsman. “I feel safe!” he shouted. “Hood’s Herald! That’s me, heh heh!” He frowned as the man made a hasty warding sign and backed away. “A joke!” Emancipor called out. “Hood’s truth—I mean, I swear by the Sisters! Health and Plague divvy my plate—I mean, fate—come back here, man! ’Twas a jest!”

Emancipor subsided into muttering. He looked around, and found that he was alone. Not a soul in sight—they’d cleared out uncommonly fast. He shrugged and turned his attention to the tarred wooden post.

The note was on fine linen paper, solitary and nailed at chest-height. Emancipor grunted. “ ’Spensive paper, that. S’prised it’s lasted this long.” Then he saw the ward faintly inked in the lower right-hand corner. Not a minor cantrip, like boils to the family of whoever was foolish enough to steal the note; not even something mildly nasty, like impotence or hair-loss; no, within the circular ward was a skull, deftly drawn. “Beru’s beard,” Emancipor whispered. “Death. This damned note will outlast the post itself.”

Nervous, he stepped closer to study the words. They showed the hand of a hired scribe, and a good one at that. Sober, he could have made inferences from all these details. Drunk as he was—and knew he was—he found the effort of serious consideration too taxing. It was careless, he knew, but when faced with returning to Subly unclothed in the raiment of the employed, he had to take the chance.

One arm on the post, he leaned closer and squinted. Thankfully, the statement was short.

Manservant required. Full time. Travel involved. Wage to be negotiated depending on experience. Call at Sorrowman’s Hostel.

Sorrowman’s... less than a block away. And “travel,” by Hood’s cowl, would mean... well, it’d mean exactly what it meant, meaning... He felt a wide grin stretching his rubbery face, until it ached with sheer delight. Coin for the wife, whilst far far away I go. School for the hairless rats, and far far away I go. Heh. Heh.

His arm slipped from the post and the next thing he knew he was lying on the cobbles, staring up at a cloudless night sky. His nose hurt, but it was a distant pain. He sat up and looked around, feeling woozy. The round was empty except for a half-dozen urchins eyeing him from an alleymouth, all looking disappointed to see him awake.

“That’s what you think,” Emancipor said as he climbed to his feet. “I’m getting me a job, right now.” He wobbled before straightening, then plucked at his coachman’s jacket and breeches—but it was too dark to see the shape they were in. Damp, of course, but that could be expected, given the heavy weave of the stiff-shouldered coat and its long, tight-cuffed sleeves. “ ’Spect they’ll have a uniform, anyways,” he muttered. “Tailored, maybe.” Sorrowman’s. That way.

The journey seemed to take forever, but he eventually made out the sign of the weeping man above the entrance to a narrow, four-storey inn. Yellow light descended from the lantern hooked under the sign, revealing a doorman leaning against the door’s ornate frame. A solid kout hung from the man’s leather belt, and one of his beefy hands moved to rest on the weapon as he watched Emancipor’s approach.

“On your way, old man,” he growled.

Emancipor stopped at the light’s edge, reeling slightly. “Got me an appointment,” he said, straightening up and thrusting out his chin.

“Not here you don’t.”

“Manservant. Got the job, I do.”

The doorman scowled, lifting a hand to scratch above his ridged brow. “Not for long, I’d say, from the look and smell of you. Mind...” He scratched some more, then grinned. “You’re on time, anyway. At least, I’m meaning, they’re awake by now, I’d guess. Go on in and tell the scriber—he’ll lead you on.”

“I’ll do just that, my good man.”

The doorman opened the door and, walking carefully, Emancipor managed to navigate through the doorway without bumping the frames. He paused as the door closed behind him, blinking in the bright light coming from a half-dozen candles set on ledges opposite the cloak rack—follower of D’rek, by the look of the gilded bowl on a ledge below the candles.

He stepped closer and looked into the bowl, to see a writhing mass of white worms, faintly pink with some poor animal’s blood. Emancipor gagged, hands pressing against the wall. He felt a rush of foamy, bitter ale at the back of his throat and—with nowhere else in range of his sight—he vomited into the bowl.

Through foam-flecked amber bile, the worms jerked about, as if drowning.

Reeling, Emancipor wiped at his mouth, then at the side of the bowl. He turned from the wall. The air was heady with some Stygg incense, sweet as rotting fruit—enough to mask the vomit, he hoped. Emancipor swallowed back another gag reflex, then drew a careful, measured breath.

A voice spoke from further in and to his right. “Yes?”

Emancipor watched as a bent, thin old man, his fingertips stained black with ink, stepped timidly into view. Upon seeing him, the scriber snapped upright, glaring. “Has Dalg that crag-headed ox gone out of his mind?” He rushed forward. “Out, out!” He shooed with his hands, then stopped in alarm as Emancipor said boldly, “Mind your manners, sir! I but paused to make an offering, uh, to the Worm of Autumn. I am the manservant, if you pl’zz. Arrived punctual, as instructed. Lead me to my employer, sir, and be quick abou’ it.” Before I let heave another offering, D’rek forgive me.

He watched the scriber’s wrinkled face race through a thespian’s array of emotions, ending on fearful regard, the black tip of his tongue darting back and forth over his dry lips. After a moment of this—which Emancipor watched with fascination—the scriber suddenly smiled. “Clever me, eh? Wisely done, sir.” He tapped his nose. “Aye. Burn knows, it’s the only way I’d show up to work for them two—not that I mean ill of them, mind you that. But I’m as clever as any man, I say, and fit to stinking drunk well suits the hour, the shadow’s cast from them two, and all right demeanor and the like, eh? Mind you,” he took Emancipor’s arm and guided him toward the stairs that led to the rooms, “you’ll likely get fired, this being your first night and all, but even so. They’re on the top floor, best rooms in the house, if you don’t mind the bats under the eaves, and I’d wager it’s rum to them and all.”

The climb and the lighter feeling in his stomach sobered Emancipor somewhat. By the time they reached the fourth landing, walked down the narrow hall and stopped in front of the last door on the right, he was beginning to realise that the scriber’s ramble had, however confusedly, imparted something odd about his new employers—new? Have I been hired, then? No, no recollection of that—and he tried to think of what it might be... without success. He came to his mind sufficiently to claw through his grey-streaked hair while the wheezing scriber softly scratched on the door. After a moment the latch lifted and the door swung silently open.

“Kind sir,” the scriber said hastily, ducking his head, “your manservant is here.” He bowed even further, then backed his way down the hall.

Emancipor drew a deep breath, then lifted his gaze to meet the cold regard of the man before him. A shiver rippled down his spine as he felt the full weight of those lifeless grey eyes, but somehow he managed not to flinch, nor drop his gaze, and so studied the man even as he himself was studied. The pale eyes were set far back in a chalky, angular face, the forehead high and squared at the temples, the greying hair swept back and of mariner’s length—long and tied in a single tail. An iron-streaked, pointed beard jutted from the man’s square, solid chin. He looked to be in his forties, and was dressed in a long, fur-trimmed morning robe—far too warm for Lamentable Moll—and had clasped his long-fingered, ringless hands in front of his silk-cord belt.

Emancipor cleared his throat. “Most excellent sir!” he boomed. Too loud, dammit.

The skin tightened fractionally around the man’s eyes.

In a less boisterous tone, Emancipor added, “I am Emancipor Reese, able manservant, coachman, cook—”

“You are drunk,” the man said, his accent unlike anything Emancipor had ever heard before. “And, your nose is broken, although it appears the bleeding has slowed.”

“My humblest apologies, sir,” Emancipor managed. “For the drink, I blame grief. For the nose, I blame a wooden post, or poss’bly the cobblestones.”

“Grief?”

“I mourn, sir, a most terr’ble personal trag’dy.”

“How unfortunate. Step inside, then, Mister Reese.”

The chambers within occupied a quarter of the top floor, opulently fitted with two large poster-beds, both covered in twisted linen, a scriber’s desk with drawers and a leather writing-pad, and a low stool before it. Bad frescos set in cheap panels adorned the walls. To the desk’s left was a large walk-in wardrobe, its doors open and nothing inside. Beside it was the entrance to a private bathing area, a bead-patterned, soft-hide curtain blocking it from view. Four battered chest-high travel trunks lined one wall; only one open and revealing fine clothes of foreign style, on iron hangers. There was no one else in the room, but somehow the presence of a second person remained to give proof to the tousled bed. The only truly odd thing in the room was a plate-sized piece of grey slate, lying on the nearest bed. Emancipor frowned at it, then he sighed and swung a placid smile at the man, who stood calmly by the door, which he now closed, setting the loop-lock over the latch. A tall one. Makes bowing easier to cheat.

“Have you any references, Mister Reese?”

“Oh yes, of course!” Emancipor found he was nodding without pause. He tried to stop, but couldn’t. “My wife, Subly. Thirty-one years—”

“I meant, your previous employer.”

“Dead.”

“Before him, then.”

“Dead.”

The man raised one thin eyebrow. “And before him?”

“Dead.”

“And?”

“And before that I was a cockswain on the able trader, Searime, for twenty years doing the Stygg run down Bloodwalk Strait.”

“Ahh, and this ship and her captain?”

“Sixty fathoms down, off Ridry Shelf.”

The second eyebrow rose to join the other one. “Quite a pedigree, Mister Reese.”

Emancipor blinked. How did he do that, with the eyebrows? “Yes, sir. Fine men, all of them.”

“Do you... mourn these losses nightly?”

“Excuse me? Oh. No sir, I do not. The day after, kind sir. Only then. Poor Baltro was a fair man—”

“Baltro? Merchant Baltro? Was he not the most recent victim of this madman who haunts the night?”

“Indeed he was. I, sir, was the last man to see him alive.”

The man’s eyebrows rose higher.

“I mean,” Emancipor added, “except for the killer, of course.”

“Of course.”

“I’ve never had a complaint.”

“I gathered that, Mister Reese.” He opened his hands to gesture with one to the stool at the desk. “Please be seated, whilst I endeavour to describe the duties expected of my manservant.”

Emancipor smiled again, then went over and sat down. “I read there’s travel involved.”

“This concerns you, Mister Reese?” The man stood at the foot of one of the beds, his hands once again clasped at his lap.

“Not at all. An incentive, sir. Now that the seas have subsided, and the blood-toll is no more, well, I itch for sea-spray, a pitching deck, rolling skylines, the tip and tumble and turn—is something wrong, sir?”

The man had begun to fidget, a greyish cast coming to his already pale face. “No, not at all. I simply prefer travelling overland. I take it you can read, or did you hire someone?”

“Oh no, I can read, sir. I’ve a talent for that. I can read Moll, Theftian and Stygg—from the chart-books, sir. Our pilot, you see, had a taste for the mead—”

“Can you scribe in these languages as well, Mister Reese?”

“Aye, sir. Both scrying and scribing. Why, I can read Mell’zan!”

“Malazan?”

“No, Mell’zan. The Empire, you know.”

“Of course. Tell me, do you mind working nights and sleeping during the day? I understood you are married—”

“Suits me perfectly, sir.”

The man frowned, then nodded. “Very good, then. The duties include arranging mundane matters related to the necessities of travel. Booking passage, negotiating with port authorities, arranging accommodation howsoever it suits our purposes, ensuring that our attire is well-maintained and scented and free of vermin, and so forth—have you done such work before, Mister Reese?”

“That, and worse—I mean, that and more, sir. I can also groom and shoe horses, r’pair tack, sew, read maps, sight by stars, tie knots, braid ropes—”

“Yes yes, very good. Now, as to the pay—”

Emancipor smiled helpfully. “I’m dirt cheap, sir. Dirt cheap.”

The man sighed. “With such talents? Nonsense, Mister Reese. You diminish yourself. Now, I will offer a yearly contract, depositing sufficient amount with a reputable money-holding agency, to allow for regular transferral of earnings to your estate. Your own personal needs will be accommodated free of charge whilst you accompany us. Is the annual sum of twelve hundred standard-weight silver sovereigns acceptable?”

Emancipor stared.

“Well?”

“Uh, uhm...”

“Fifteen hundred, then.”

“Agreed! Yes indeed. Most assur’dly, sir!” Hood’s Breath, that’s more than Baltro makes—I mean, ‘made.’ “Where do I sign the contract, sir? Shall I begin work now?” Emancipor rose to his feet, waited expectantly.

The man smiled. “Contract? If you wish. It is of no concern to me.”

“Uhm, what shall I call you, sir? Sir?”

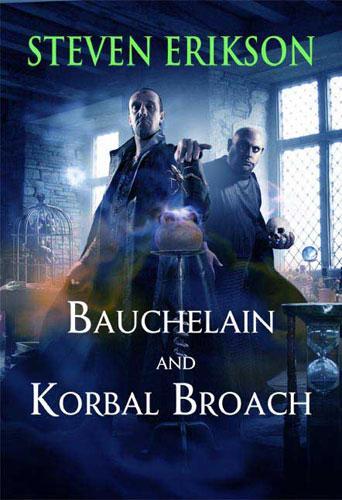

“I am named Bauchelain. Master will suffice.”

“Of course, Master. And, uh, the other one?”

“The other one?”

“The one you travel with, Master.”

“Oh,” Bauchelain turned away, his gaze falling to rest pensively on the slab of slate. “He is named Korbal Broach. A very unassuming man, you might say. As manservant, you answer to me, and me alone. I doubt whether Master Broach foresees a use for you.” He turned and smiled slightly, his eyes as cold as ever. “Of course, in that I could be wrong. We’ll see, I imagine, won’t we? Now, I wish a meal, with meat, rare, and a dark wine, not overly sweet. You may place your order with the scriber below.”

Emancipor bowed. “At once, Master.”

GULD STOOD ATOP DEAD SEKARAND’S CREAKING tower and scanned the city, squinting to see through the miasmic woodsmoke that hung almost motionless over the rooftops. The stillness below contrasted strangely with the night-clouds over his head, tumbling, rolling on out to sea, seeming so close above him that he found he’d instinctively hunched down as he leaned on the moss-slick parapet and waited, with dread, for the lantern signal poles to be raised.

It was the call of the season, when the sky seemed to heave itself over, trapping the city in its own breath for days on end. The season of ills, plagues, rats driven into the streets by the dancing moon.

Dead Sekarand’s Tower was less than a decade old, yet already abandoned and known to be haunted, but Guld had little fear, since he himself had been responsible for tending and nurturing the black weeds of hoary rumour—it suited the new purpose he’d found for the dull-stoned edifice. From this almost-central vantage point, his system of signal poles could be seen in any section of Lamentable Moll.

In the days when the Mell’zan Empire had first threatened the city-states of Theft—mostly on the other coast, where the Imperial Fist Greymane had landed his invasion force, coming close to conquering the entire island before being murdered by his own troops—in the days of smoke and threatening winds, Sekarand had come to Lamentable Moll. Calling himself a High Sorceror, he had contracted with King Seljure to aid in the city’s defense, and had raised this structure as his spar of power. What followed then was confused and remained so ever since, though Guld knew more details than most. Sekarand had raised liches to keep him company within these confines, and they’d either driven him mad, or murdered him outright—Sekarand had flung himself, or had been thrown, from these very merlons, down to his death on the cobbles below. Grim jokes about the High Sorceror’s swift descent had run through the streets for a time. In any case, like the Mell’zans—whose presence on Theft remained in but a single, downtrodden port on the northwest coast with half a regiment of jaded marines—Sekarand had been a promise unfulfilled.

Guld had used the tower for three years now. He’d seen a few shades, all of whom vowed service to a lich who dwelt under the tower’s foundations, but apart from proferring this tidbit of information, they’d said little and had never threatened him, and the nature of their service to the lich remained a mystery.

It had been Guld who’d asked them to moan and howl occasionally, keeping the plunderers and explorers at bay. They’d complied with tireless dedication.

The clouds felt heavy overhead as Guld waited—as if bloated with blood. The sergeant stood unmoving, expecting at any moment the first drops of something to come spattering against his face.

After a while, he sensed a presence beside him and slowly turned to find a shade hovering near the trapdoor.

Clothed in wispy rags, ghostly limbs sporting knotted strips of sailcloth, twine and faded silk—all that held it to this mortal world—its black-pit eyes, set in a pallid face, were fixed on the sergeant.

Guld sensed, with sudden alarm, that the shade had been but moments from launching itself at his back. One shove, and over I’d go....

Discovered, the ghostly figure now slumped, grumbling to itself.

“Pleased with the weather?” Guld asked, fighting down a chill shiver.

“An air,” the shade rasped, “to smother sound and scent. Dull the vision. Yet it dances unseen.”

“How so?”

“Among the Warrens, this air dances bright. My master, my lord, lich of liches, supreme ruler, He Who Awakened All Groggy after centuries of slumber but is now Bursting With Wit, my master, then, sends me—me, humourless serf, humble savant of social injustices, injustices that persist no doubt to this day, me, then, I come with a warning by his insistent command.”

“A warning? Is this weather fed by sorcery?”

“A hunter stalks the dark.”

“I know,” Guld growled. “What else,” he asked without expecting a comprehensible answer, “do you sense about him?”

“My master, my lord, lich of—”

“Your master,” Guld interrupted, “what of him?”

“—liches, supreme ruler, He Who—”

“Enough of the titles!”

“—Awakened All Groggy after—”

“Shall I call on an exorcist, shade?”

“If you’d not so rudely interrupted I’d be done by now!” the ghost snapped. “My master, then, has no desire to be among the hunted. There.”

Guld scowled. “Just how nasty is this killer? Never mind, you’ve answered me, haven’t you? At the moment, I can’t stop him, whoever he is. If he chooses to ferret out your master, well, I can only wish the lich luck.”

“Amusing,” the shade grumbled, then slowly vanished.

Amusing? The shades of this tower are damned odd, even for shades. In any case, keeping mulling, Guld. Lamentable Moll’s known for its sorcerors, its diviners and readers, its warlocks and well-sounders, seers and the like, but it’s mostly small fish—nobody’s ever claimed Theft to be an island of high civilisation. In Korel it’s said a demon prince runs a merchant company, and in the old city-swamps of the lowbeds the undead are as common as midges. Glad I don’t live in Korel. What was I thinking about? Oh, yes, suspects....

Nothing else of note marked the next hour. The fourth bell after midnight came and went. Even so, Guld was not surprised a short time later when three wavering lights rose in panicked haste above the dark buildings in a nearby quarter. The twelfth. Unending, each night.... Maybe Stul Ophan had been right—the beacons rose from the estate district, from the nobility’s pinched, bloodless heart.

He spun from the merlon and took a step to the trapdoor, then stopped, the shock of rain against his brow sending a superstitious chill through his bones. A moment later he shook himself. Not blood. Just water, nothing more. Nothing more. He pulled up the heavy wooden door with an angry wrench, and quickly plunged down into the darkness below.

The shades set up a howl all the way down, and this time, Guld knew that their gelid moans, ringing from the stone walls on all sides, had nothing to do with keeping thieves and adventurers at bay.

AN HOUR BEFORE DAWN, BAUCHELAIN INSTRUCTED Emancipor to ready his bed. Of the other man—Korbal Broach—there’d been no sign, which did not seem to perturb Bauchelain, who’d spent the night inscribing sigils and signs on the piece of slate. Bells, bells on end at the desk, the man hunched over the grey stone. Etching and scribing, muttering under his breath, and consulting from a half-dozen leather-bound books—each worth a year’s wage in paper alone.

Emancipor, hungover and dead tired, puttered here and there in the room, once he’d had the remains of the supper removed, tidying up as best he could. He found in Bauchelain’s travel chest a finely made hauberk of black-iron chain, long-sleeved and knee-length, which he oiled from a kit, using spare wire to repair old damage—cut and crushed links—the coat had known battle, and so too the man who owned it. And yet to look at him, as Emancipor often did from the corner of his eye, it was hard to believe Bauchelain had ever been a soldier. He scribed and mumbled and squinted and occasionally poked out his tongue as he worked over the slate. Like an artist, or an alchemist, or a sorceror.

A damned strange way to pass the night, Emancipor concluded. He bit back on his curiosity, which grew more tempered with his suspicions that the man indeed was a practitioner in the dark arts. The less gleaned the better, I always say.

He finished with the mail coat and, grunting under its slippery weight, returned it to its perch. As he adjusted the inside-padded shoulders on the heavy hanger, he noticed a long, flat box positioned below the coat-hooks. It had a latch, but was otherwise unlocked. He removed it, grunting again at its weight, and set it on the spare bed. A glance over at Bauchelain assured him that his master was taking no heed, so Emancipor unlatched the lid and lifted it away, to reveal a dismantled crossbow, a dozen iron-shod quarrels, and a pair of mail gauntlets open at the palm and the finger-tips.

His memory swept him back to his youth, on the battlefield that would in legend be known as Estbanor’s Grief, where the rag-tag militias of Theft—before each city found its own king—had thrown back an invading army from Korel. Among the Korelri legions were soldiers who carried Mell’zan weapons—each superbly made and superior to anything local. This was such a weapon, made by a master smith, constructed entirely of hardened, tempered iron—maybe even the famous D’Avorian Steel—even the stock was metal. “Hood’s Breath,” Emancipor whispered, running his fingers over the pieces.

“ ’Ware the heads,” Bauchelain murmured, having come up to stand behind Emancipor. “They kill at a touch, if blood be drawn.”

Emancipor’s hand recoiled. “Poison?”

“You think me an assassin, Mister Reese?”

Emancipor turned and met the man’s amused gaze.

“In my days,” Bauchelain said, “I’ve been many things... but poisoner is not among them. They are invested.”

“You’re a sorceror?”

Bauchelain’s lips quirked into a smile. “Many people call themselves that. Do you follow a god, Mister Reese?”

“My wife swears by ’em—I mean, uh, she prays to a few, Master.”

“And you?”

Emancipor shrugged. “The devout die too, don’t they? Clove to an ascendant just doubles the funeral costs, ’sfar as I can see, and that’s all. Mind, I’ve prayed fierce on occasion—maybe it saved my skin, but maybe it was just my cast to slip Hood’s shadow so far....”

Bauchelain’s gaze softened slightly, lost its focus. “So far...” he said, as if the words were profound. Then he clapped his manservant on the shoulder and returned to his desk. “A long life is yours, Mister Reese. I see no shadow’s shadow, and the face of your death is a distant one.”

“The face?” Emancipor licked his lips, which had become uncommonly dry. “You, uh, you divined my moment of death?”

“As near as one can,” Bauchelain replied. “Some veils are not easily torn aside. But I think I have as much as needed.” He paused, then added, “Even so, the weapon needs no cleaning. You may return it to its trunk.”

Not just a sorceror, then. A Hood-stained, death-delving necromancer. Damn you, Subly, the things I do.... He replaced the lid and set the latches. “Master?”

“Hmm?” Bauchelain was busy over his slab again.

“My face at death—did you see it truly?”

“Your visage? Yes, as I said.”

“Was it, was it a face of fear?”

“No, surprisingly. It seems you die laughing.”

“DIE LAUGHING,” EMANCIPOR MUTTERED AS HE STUMbled his way down the empty, dark streets, seeing only his soft, Subly-warmed bed hovering in his mind’s eye. “That’s likely a damned lie, I’d say, unless I quit—get as far away from that death-dealer as I can. Queen of Dreams, what a mess I’m in. It’s the Lad o’ Luck for certain, not the Lady. It’s the push, not the pull. I was drunk—too drunk to sniff it all out, and then it was too late. He’s seen my death, too. He has me. I can’t quit. He’ll send something after me—a ghoul, or a k’nip-trill, or some other damned spectre—to tear my heart out, and Subly’d be cursing the blood-stained sheets down at Beater’s Rock an’ all the lye she’d have to buy and that’d be a curse to my name even then, with me dead and gone and the brats fighting o’er my new boots and—”

He stopped with a grunt as he walked clean into another man, whose body felt as solid as a bale of hides, and who—as Emancipor stepped back in alarm—was as big as a half-blooded Trell. “M’pardon, sir,” Emancipor said, ducking his head.

The man raised a black-mailed arm, at the end of which was a massive, flat, pale and soft-looking—almost delicate—hand.

Emancipor took another step back as the air between them seemed to crackle and something tugged hard at his guts.

Then the hand twitched, the fingers fluttered, and the arm slowly dropped back down. A soft giggle came from under the stranger’s hood. “Sweet fate, he’s marked for me,” he said in a high, quavering voice.

“I said my pardon, sir,” Emancipor said again. He realised he was in the Estate District, having gone by the shortest route between Sorrowman’s and his house—damned stupid, what with blood-hungry private guards patrolling the nobles’ quarter, determined to catch the mad killer for their masters, and the rewards to follow. “If you’ll let me pass, sir,” Emancipor said, moving to step past. There was no one else about, and dawn was still a quarter-bell away.

The stranger giggled again, then said, “Such a mark, saving. You felt the chill, then?”

Damned strange accent. “It’s a hot enough night,” he mumbled as he hurried by. The stranger let him go, but Emancipor felt cold eyes on his back as he walked down the street.

A moment later he was surprised to see a cloaked figure hurrying its way down the other pavement—small, feminine. Then he was further startled by the passage of an armoured man, rustling and softly clanking, moving along on the woman’s trail. Hood’s Herald, the sun’s not even up yet!

He suddenly felt very tired. Somewhere ahead, he now saw, was a commotion of some kind. He saw lantern lights, heard shouting, then a woman’s scream. He hesitated, then took a side route that’d take him around the scene, and back onto more familiar ground.

Emancipor felt clammy under his clothes, as if he’d just brushed... something unpleasant. He shook himself. “Better get used to it, working nights and all. Anyway, I was safe enough—no chance of laughing this damned night, that’s for sure.”

“A MESSY ONE,” THE CHALK-FACED GUARD MUTTERED, wiping across his mouth with the back of his hand.

Guld nodded. It was the worst he’d seen yet. Young Lordson Hoom, ninth-removed from the throne’s own blood, had died ignobly, with most of his insides strewn and smeared halfway down the alley.

And yet no one had heard a sound. The sergeant had come upon the scene less than a quarter-bell after the two patrol guards had themselves stumbled onto it. The blood and bits of flesh weren’t yet cold.

Guld had sent off the tracking dogs. He’d dispatched his corporal to the palace with two messages—one to the king, and the other—far less softly worded—to Magus Stul Ophan. With the exception of his squad detachment and a lone terrified horse still hitched to the Lordson’s overturned carriage—overturned. Hood’s breath!—there was only one other person present at the scene, and that presence had Guld deeply, profoundly, worried.

He finally turned his gaze from the carriage to study the woman. Princess Sharn. King Seljure’s only child. His heir, and, if the rumours are true, a real dark piece of work in her own right.

Though it would mean trouble later, Guld had insisted on detaining the royal personage. After all, it’d been her screaming that had drawn the patrol, and the question of what the princess was doing out in the city well after the night’s fourth bell—with no guard, not even her maid-in-waiting—needed answering.

His eyes narrowed on the young girl. She was wrapped in a voluminous cloak, hooded with her face hidden in shadows. She’d regained her composure with alarming ease. Guld scowled, then approached her. He jerked his head to the two guardsmen flanking the princess, and they moved away.

“Highness,” Guld began, “your calm is an impressive example of royal blood. Frankly, I’m awed.”

She acknowledged this with a slight tilt of her head.

Guld rubbed at his jaw, glancing away for a moment, then swung upon her an intense professional expression. “I am also relieved, for it means I can question you here and now, whilst your memory remains fresh, unclouded—”

“You are presumptuous,” the princess said in a light, bored tone.

He ignored that. “It’s clear you and Lordson Hoom were involved in a clandestine relationship. Only this time, either you came later, or he came early. For you, then, a pull of the Lady. For the lad, a push of the Lord. I can imagine your relief, Princess, not to mention your father’s—who will have been duly informed by now.” He paused at hearing her quickly drawn breath. “So, what I need to know is what you saw, precisely, upon arriving. Did you see anyone else? Did you hear anything? Smell anything?”

“No,” she answered. “Hoomy was... was already, uh, like that,” she gestured toward the alley behind Guld.

“Hoomy?”

“Lordson Hoom, I mean.”

“Tell me, Princess, where is your handmaid? I can’t believe you would come here entirely alone. She’d be your messenger in this affair, obviously, since I imagine the secret love notes flew fast and often—”

“How dare you—”

“Save that for your cowering underlings,” Guld snapped. “Answer me!”

“Do nothing of the sort!” a voice commanded behind the sergeant.

He turned to see Magus Stul Ophan pushing his way past a line of guards at the alleymouth. It was nearing dawn, and the fat man’s arrival was peculiarly accompanied by the day’s first birdsong. “Highness,” Stul said, inclining his head, “your father the King wishes to see you immediately. You may take my carriage.” Stul turned a dagger glare on Guld. “The sergeant is, I believe, done with you.”

Both men stepped back as Princess Sharn hurried past and quickly disappeared inside the carriage. As soon as the door closed and the driver flicked the horses into motion, Guld rounded on the Magus. “Now, I gather that Lordson Hoom was anything but an appropriate hay-roller for the precious princess, and I can imagine that Seljure wants to bury any royal involvement in what’s happened here—but if you ever again step between me and my investigation, Ophan, I’ll leave what’s left of you for the crabs. Understood?”

The Magus went red, then white. He spluttered, “The King’s command, Guld—”

“And if I’d found him standing here over the lad’s mangled corpse, I’d be no less direct in my questioning. The king is one man—his fear is nothing compared to the city’s fear. And you can tell him, if he wants anything left to rule, he’d best stay out of my way and let me do my job. Gods, man, can’t you feel the panic?”

“I can! Burn’s Blood, I damned well share it!”

Guld took a handful of Stul Ophan’s brocaded cloak and pulled the man to the alley. “Take a long look, Magus. This was managed in silence—neither estate to each side awoke—even the garden hounds remained silent. Tell me, what did this?” He released Stul Ophan’s cloak and stepped back.

The air turned icy around the magus as he hastily cast a series of cantrips. “A spell of silence, Sergeant,” he rasped. “The lad screamed all right, gods how he screamed. And the air itself was closed, folded in on itself. High sorcery, Guld, the highest. No smell could escape to afright the dogs on the other sides of these walls—”

“And the carriage? It has the look of having been rammed, as if by a mad bull. Scry the horse, dammit!”

Stul Ophan staggered up to the quivering, lathered animal. As he reached up one hand the horse reared back, eyes rolling, ears flattening against its skull. The magus swore. “Driven mad! Its heart races but it cannot move. It will be dead within the hour—”

“But, what did it see? What image remains behind its eyes?”

“Obliterated,” Stul Ophan said. “Wiped clean.”

They both turned as the fast-approaching sound of shod hooves on the cobblestones. An armoured rider appeared, boldly pushing his white charger past the guards—Hood, what’s the point of having a cordon of guards? The newcomer wore a white fur-lined cloak, a white-enamelled iron helm, and a coat of silver mail. The pommel at the end of his broadsword looked to be a single polished opal.

Guld cursed under his breath, then called out to the rider. “What brings you here, Mortal Sword?”

The man reined in. He removed his helmet to reveal a narrow, scarred face and close-set eyes that glittered black. Those eyes now turned to the lantern-lit scene in the alley. “The foulest of deeds,” he rasped, his voice thin and ragged—the story went that a Drek assassin’s dagger had come near to opening the man’s throat a dozen years back—but Tulgord Vise, Mortal Sword to the Sisters, had survived, while the assassin hadn’t.

“This is not a religious matter,” Guld said, “though I thank you for your vow to scour the nights until the killer is found—”

“Found, sir? Carved into pieces, this I have sworn. And what do you, cynical unbeliever, know of matters of faith? Do you not smell the stench of Hood in this? You, Magus, can you deny the truth of my words?”

Stul Ophan shrugged. “A necromancer—most certainly, Mortal Sword, but that doesn’t perforce mean a worshipper of the God of Death. Indeed, the priesthood disavows necromancy. After all, those dark arts are an assault on the Warren of the Dead—”

“Political convenience, that disavowal. You are a spineless, mewling fool, Ophan. I have crossed swords with Hood’s Herald, or do you forget?”

Guld noted one of his guardsmen flinch at that. “Tulgord Vise,” the sergeant said, “Death was not the goal here—hasn’t been all along.”

“What do you mean, sir?”

“I mean the killer is... collecting—”

“Collecting?”

“Parts.”

“Parts?”

“Organs, to be more precise. Ones generally considered vital to life, Mortal Sword. Their removal results in death as a matter of course. Do you see the distinction?”

Tulgord Vise leaned on the horn of his saddle. “Semantics are not among the games I play, sir. If only organs are required, why then the destruction of souls?”

Guld turned to the magus. “Destruction, Stul Ophan?”

The man shrugged uneasily. “Or... theft, Sergeant, which is of course more difficult....”

“But why steal souls, if destroying them more easily serves the purpose of ensuring your inability to question them?”

“I don’t know.”

Tulgord Vise settled back in his saddle, one gauntleted hand resting on his sword. “Do not impede me, sir,” he said to Guld. “My blade shall deliver what is just.”

“Better the madman writhe on the hooks,” Guld replied, “unless you feel sufficient to the task of quelling a city’s bloodlust.”

This silenced the Mortal Sword, if only briefly. “They will sit well with my deed, sir—”

“It won’t be enough, Mortal Sword. Better still if we drag him through every street, but it’s not up to me. In any case,” Guld added, stepping forward, “it’s you who’d best stay out of my way. Interfere with me at your peril, Mortal Sword.”

Tulgord Vise half-drew his weapon before Stul Ophan leapt close and stilled the man’s arm.

“Tulgord, ’tis precipitous!” the magus bleated.

“Remove your feeble grip, swine!”

“Look about you, sir. I beg you!”

The Mortal Sword glanced around, then slowly resheathed his weapon. Clearly, unlike Stul Ophan, he hadn’t heard the locking of six crossbows, but the weapons were trained on him now, and the expressions on the faces of Guld’s squad left no doubt as to their intent.

The sergeant cleared his throat. “This is the twelfth night in a row, Mortal Sword. It has, I believe, become very personal to my men. We want the killer, and we’ll have him. So again, stay out of my way, sir. I seek no insult to you or your honour, but draw your blade again and you’ll be dropped like a rabid dog.”

Tulgord Vise kicked Stul Ophan away, then wheeled his mount. “You mock the gods, sir, and for that your soul will pay.” He put spurs to the charger’s flanks and rode off.

The moment was closed by the sudden collapse of the carriage horse, followed immediately by the heavy snap of quarrels released in the animal’s direction. Guld winced as the six bolts buried themselves in the horse’s body.

Dammit, those fingers itched, didn’t they. He swung a sour look on his sheepish men.

Stul Ophan occupied the embarrassed moment by straightening his clothing. Then he said without looking up, “Your killer’s a foreigner, Sergeant. No one in Lamentable Moll is of this high order in necromancy, including me.”

Guld acknowledged his thanks with a nod.

“I’ll report to the king,” the magus said as his own carriage returned, “to the effect that you’ve narrowed your list of suspects, Sergeant. And I shall add my opinion that, barring interference, you’re close to your quarry.”

“I hope you’re right,” Guld said in a moment of honest doubt that clearly startled Stul Ophan, who simply nodded then walked to his carriage.

Guld waited until the man left, then singled out one of his guards and pulled him to one side. He studied the young man’s face. “Death’s Herald crossed your trail, then?”

“Sir?”

“I saw you react to Vise’s words. Of course, he meant someone else in that sordid role, since it’s a claim he’s made for twenty years. But what did you hear in those words?”

“A superstition, Sergeant. A drunken old man, earlier this night, down in the wharf district—he called himself that, is all. Was nothing, in truth—”

“What was the man doing?”

“Reading a posted notice in Fishmonger’s Round, I think. It’s still there, warded, I heard.”

“Likely nothing to it, then.”

“As the gods decree, sir.”

Guld narrowed his gaze, then grunted. “Fair enough. Once I’ve done reporting to the king, let’s take a look at this notice.”

“Yes, sir.”

At this moment the dogger returned with his hounds. “It’s a mess,” he reported. “By their tuck they found a woman’s trail, or a man’s, or both, or neither. One, or two, then a third, heavy I’d say that last one with brine and sword-oil, or so the dogs danced, anyway.”

Guld studied the six hounds on their limp leashes, their heads hanging, their tongues lolling. “Those trails. Where did they all lead?”

“Lost them down in the wharfs—y’got rotting clams and fish guts to contend with, eh? Or else the trails were magicked. My children here all closed in on a sack of rotting fish—not like ’em, I say, not like ’em at all.”

“From the smell, your hounds did more than just close in on that sack of rotting fish.”

The dogger frowned. “We thought we might do better hiding our scent, sir.”

Guld stepped closer to the man, then flinched back. Hood take me, wasn’t just the dogs that rolled in those fish! He stared at the dogger.

The man looked away, licking his lips, then yawning.

SUBLY’S VOICE CAME FROM THE MAIN ROOM. “Pigeons! They’re roosting over our heads, in the eaves, in the drain pipes—why haven’t you done anything about it, Emancipor? And now... and now, oh, Soliel forfend!”

It was a voice that could penetrate every corner of their house. A voice from which there was no domestic escape. “But soon...” Emancipor whispered, knowing his mood was miserable from lack of sleep and too much drink the night before, knowing he was being unfair to his poor wife, knowing all these things but unable to stop the dark torrent of his thoughts. He paused to examine in the tin mirror the blur of his lined face and the bloodshot eyes, before setting the blade once again to his whiskers.

The brats whined from their loft, their scratching so loud he could hear every scrape of grubby nails against flesh. They’d been sent home, both with the mange. Their mother was... mortified. There’d be need for an alchemist—at great expense—but the damage was done. The foul-smelling skin mould that was the curse of dogs and lowly street urchins had invaded their home, befouling their position, their prestige, mocking their pride. A bowlful of gold coins in Soliel’s temple could not reverse the disaster. And for Subly the cause was clear—

“The pigeons, Emancipor! I want them out! You hear me?”

She’d been in a good enough mood earlier in the day, doing a poor job of hiding her shock at his finding work so swiftly, and an even poorer job of disguising the avaricious glint that came into her eyes when he explained the financial arrangements that had already been made. For these rewards, Subly had yet to take the broom to him, driving him out into the muddy, garbage-strewn, slate-filled backyard to deal with the pigeons. She’d even allowed him an extra hour of sleep before wailing in horror at their children’s ignoble return from the tutor’s.

They could afford the alchemist, now. They could even afford to move closer to the school, into a finer neighbourhood, full of proper people thus far spared Subly’s dramatic life.

He told himself he shouldn’t be so mean—after all, she’d stood by him all these years. “Like a mountain...” And she’d had her own past, dark and messy and tainted with blood. And she’d done her share of suffering since, though not so much as to prevent her begetting two whelps during the years he’d mostly spent at sea. Emancipor paused again in his shaving to scowl. That had always nibbled at his insides, especially since neither child looked much like him. But he’d done his part raising them, so in a way it didn’t matter. Their contempt for him was truly and surely sufficient proof of his fatherhood, no matter the blood’s mix.

Emancipor washed the crusty suds from his face. Maybe tonight he’d meet the other man, the mysterious Korbal Broach. And he’d have his new uniform measured, and his travelling kit assembled.

“I want the traps set, Emancipor Reese! Before you leave, you hear me?”

“Yes, dear!”

“You’ll stop at the alchemist’s?”

He rose from the stool and reached to the bed-post for his coat. “Which one? N’sarmin? Tralp Younger?”

“Tralp, of course, you oaf!”

Add another two silver crowns to the cost, then. She’s already getting comfortable with the new state of affairs....

“Set the traps! Hood’s Herald visit those damned pigeons!”

Emancipor frowned. Hood’s Herald. Something, yesterday.... He shook his head and shrugged. “Curse of the ale,” he muttered, as he turned to the hanging covering the bedroom entrance. “Dear Subly... The mountain that roars... but soon, so very soon...”

THE KING HAD SHOWN HIM FEAR. IN ELDER DAYS that would have condemned Guld to the assassin’s knife. But Seljure was an old man, now—older than his years. His Highness had found tremulous uncertainty his bedmate, now that the concubines had been sent away. The king’s tight-skinned, snaked-eyed advisors remained, of course, but even they hadn’t been present for Guld’s report. Even so, if they caught a sniff—the king had shown his fear, not just of the killer in the city, but of the dark storm brewing in Stygg, and the rumbles from the Korelri Compact to the south. The king had... babbled. To a simple sergeant of the guard. And Guld now knew more about the precious Princess Sharn than he’d care to.

He shrugged to himself as he strode down the narrow, winding and barrow-humped Street of Ills, on his way to Fishmonger’s Round. Twilight had descended on Lamentable Moll, in every way, it seemed. In any case, he’d done his duty, made his report to King Seljure; he received the expected instructions to quell the rumours of the royal involvement. Lordson Hoom’s father, a landholder of some clout, had been taken care of—with a chestful of coin and promises, no doubt, and Guld had returned to the city’s quiet, tense streets.

He’d left the corporal standing guard over the posting, even though the death ward made the notice’s theft highly unlikely. Guld had been forced to await the audience with Seljure for most of the day, and now the sun was low in the sky over the bay. News of the noble son’s murder had deepened the fearful pall over the city; already the shops were closing up, the streets emptying, because tonight there would be hired killers out—shadowy extensions of noble wrath—indiscriminate with a vengeance. Tonight, anyone foolish enough to remain on the streets without good cause (or a bristling squad of bodyguards) was likely to get his entrails pulled out, if not worse.

Guld turned a corner and approached the Round. His corporal—standing nervously with a hand on his short-sword—was the only occupant left, save one skinny dog, a bedraggled crow perched atop the post, and a dozen seagulls squabbling over something in the sewer trench.

A breeze had come in from the sea, only marginally cooler than the turgid, sweltering heat in the city. Guld wiped sweat from his upper lip and walked up to his corporal.

“Anyone take the measure of you, lad?”

The young man shook his head. “No, sir. I’ve been here all day, sir.” Guld grunted. “Sorry, I was delayed at the king’s palace. Feet tired?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Well then, let’s exercise them—you have the address from the notice?”

“Yes, sir. And I heard from a rat-hunter that there’s two of them, foreigners, who came in on the Mist Rider....”

“Go on.”

The corporal shifted weight. “Uh, well, the Mist Rider last called out of Korel, and has since picked up cargo after unloading some iron, and left for Mare this morning. Oh, and the foreigners hired their manservant.”

“Oh?”

“Yes, sir, and he was the coachman for Merchant Baltro, sir. Imagine that.”

Guld scowled. “All right, lad, let’s go then.”

“Yes sir. Sorrowman’s Hostel. It’s not far.”

DALG THE DOORMAN GRINNED KNOWINGLY AT Guld. “Ain’t s’prised you come, Sergeant, ain’t s’prised at all. Come to see Obler, eh? Only he’s retired. Ain’t lending money no more, least not as I can see, and—”

Guld cut in, “You have a pair of guests. Foreigners.”

“O-Oh, yes, them. Odd pair.”

“What’s odd about them?”

The doorman frowned and scratched his head. “Well,” he said. “You know. Odd. One of ’em never leaves the room, eh?”

“And the other one?”

“Not so often neither, and hardly at all now that they got their manservant. Oh, they don’t visit nobody and nobody visits them, and they eat in their room, too.”

Guld nodded. “So, are they both in right now?”

“Yes, sir.”

The sergeant left the corporal with the doorman and entered Sorrowman’s. He was immediately confronted by the hostelier, who approached with an offerings bowl and a cloth in his hands. He quickly set the bowl on a ledge and tucked the cloth into his belt. “Guardsman, can I help you?”

Guld watched the man’s long, blackened fingers begin weaving a nervous pattern as they clasped and unclasped at the hostelier’s lap. “Obler, isn’t it? Keeping honest these days?”

The man blanched. “Oh yes indeed, Guardsman. For years! Run this establishment, y’see, and do scribing on the side. I’m respectable now, sir. Upstanding and all, sir.” Obler’s eyes darted.

“I want to speak to your two foreign guests, Obler.”

“Oh! Well, I’d best get them, then.”

“I’ll go with you.”

“Oh! Very well, follow me, sir, if you will.”

They headed up the narrow, heavily carpeted stairs, strode down the hallway. Obler knocked on the door. They waited a moment, then an old man’s voice spoke from the other side.

“What is it, Obler?”

The scriber leaned close to Guld. “That’s Reese,” he hissed. “The manservant.” He then called, “A guardsman to speak with your masters, Reese. Open, if you please.”

Guld glared at Obler. “Next time,” he rasped, “just get them to open the damned door.” He could hear the murmurs of conversation from within, and he reached up a hand to more forcefully pound on the door when it suddenly opened and the manservant quickly slipped out into the hallway, then shut the door once again behind him.

Emancipor’s eyes widened as he looked up and recognised the sergeant.

“Emancipor Reese,” Guld drawled. “I questioned you not two days ago, and now here you are again. How strange.”

“A man needs work,” Reese grumbled. “Nothing more to it.”

“Did I say there was?”

“You said ‘strange,’ but it’s nothing strange about it, ’cepting you coming here.”

Huh, the old bastard’s got a point. “I wish to speak with your masters. You may announce me now, or whatever it is they want you to do.”

“Ah, well, Sergeant. My master regrets to inform you he’s not receiving guests this evening, as he is at a crucial juncture in his research—”

“I’m not here as a guest, old man. Either announce me or step aside. I will speak to the men within.”

“There’s but one within,” Reese said. “Master Bauchelain is a scholar, Sergeant. He wishes no distractions—”

Guld growled and tried to push Reese aside, but the old man planted his feet and stood his ground. The sergeant was surprised at Reese’s deceptive strength, until he saw the old sword-scars on his right forearm. Damned veteran. I hate dealing with veterans—they don’t buckle. Guld stepped back, placing a hand on his sword. “You’ve done more than should be expected, Reese, protecting your master’s wish for privacy. But I’m a sergeant of the City Watch, and this is an official visit. If you impede me further, you’ll end up in the stock, Reese.” Guld felt his body tense as Reese’s lined face darkened dangerously. Damned veteran. “Don’t make this messy. Don’t.”

“If I let you in, Sergeant—” Reese’s voice was like gravel shifting in the surf, “I’ll likely get fired. A man needs to work. I need this job, sir. I ain’t had the best of luck, as you know. I need this job, and I mean to keep it. If you’ve questions, maybe I can answer ’em, maybe I can’t, but I won’t let you pass.”

“Hood’s breath,” Guld sighed, taking another step back. He turned to Obler, who had begun whimpering and throwing futile gestures at the two men. “Get my corporal, Obler. He’s out front. Tell him: double-time, weapon out. Understood?”

“Oh! I implore you—”

“Now!” The scriber scurried down the hall. Guld swung back to Reese, who looked resigned. The sergeant spoke quietly, “My corporal, Reese, will make a lot of noise coming up here. You’ll be disarmed and restrained. Loudly. You’ll have done all you could. No master worth his salt will find cause to fire you. Do it my way, Reese, and you’ll not get arrested. Or killed. Otherwise, we’ll work through you—we’ll take our time, until your breath is short and you’re done, then we’ll cut you down. Well, which way is it to be?”

Reese sagged. “All right, you bastard.”

They heard the corporal’s heavy boots on the stairs, the clatter of his scabbard as it struck the railing spokes, then his gasps as he appeared at the landing, his blade held out in front of him, his face flushed. The lad’s eyes widened upon seeing his sergeant and the manservant standing calmly watching him, then he ran forward as Guld waved him on.

Guld turned back to Reese. “All right,” he whispered, “make it sound convincing.” He reached out and grasped Reese by the coat’s brocaded collar. The old man bellowed, throwing a boot back to hammer the door, rattling it in its frame. Guld pulled Reese to one side and pushed him up against the wall. The corporal arrived.

“Your sword to the bastard’s neck!” Guld ordered, and the corporal complied with undue zeal, nearly slitting Reese’s throat until Guld pulled the lad’s arm back in alarm.

At that moment the door opened. The man in the threshold took in the scene in the hallway with one lazy, cool glance, then met Guld’s stare. “Release my servant, sir,” he said softly.

Guld felt a chill race along his veins. This one’s for real. The sergeant gestured at his corporal. “Step back, lad.” The guard, confused, did as he was told. “Sheathe,” Guld commanded. The sword slid into its scabbard with a rasp and click.

“That’s more agreeable,” the foreigner said. “Please come in, Sergeant, since you seem so eager to meet me. Emancipor, join us, please.”

Guld nodded to his corporal. “Wait out here, lad.”

“Yes sir.”

The three men entered the room, Reese closing the door and dropping the latch.

Guld looked around. A desk cluttered with... slabs of slate; the remains of a breakfast on a chair, recently finished. Odd, it’s near sunset. Two slept-in beds, travel trunks, only one open and revealing a city-dweller’s clothes, a coat of mail—a weapon box beneath it—and a false backing. The other three trunks were securely locked. Guld took a step closer to the desk, eyeing the slate. “I don’t recognise those runes,” he said, turning to the austere man. “Where are you from?”

“A distant land, Sergeant. Its name would, alas, mean nothing to you.”

“You have a facility for languages,” Guld noted.

The man raised an eyebrow. “Passing only. I understand my accent is, in fact, pronounced.”

“How long since you learned Theftian?”

“That is this language’s name? I thought it was Mollian.”

“Theft is the island. Moll is a city on it. I asked you a question, sir.”

“It’s an important one, then? Very well, about three weeks. During our passage from Korel, I hired one of the crewmen to instruct me—a native of this island. In any case, the language is clearly related to Korelri.”

“You are a sorceror, sir.”

The man assented with a slight nod. “I am named Bauchelain.”

“And your travelling companion?”

“Korbal Broach, a freed eunuch, sir.”

“A eunuch?”

Bauchelain nodded again. “An unfortunate practise among the people from whom he hails, done to all male slaves. For obvious reasons, Korbal Broach desires solitude, peace and quiet.”

“Where is he, then? In one of the trunks?”